How to squander a $10 million donation from a dead man

By Jill Castellano and Brad Racino

Feb. 12, 2020

In the fall of 2015, a San Diego philanthropist died of cancer and left behind millions of dollars for one of America’s premier research institutions, the University of California San Diego. The gift set off a chain reaction that led to institutional infighting, harsh whistleblower complaints and a year-and-a-half long internal investigation that is still ongoing.

What happened isn’t a simple story. After Charles “Skip” Kreutzkamp died, his family trust donated $10 million to the university. More than half the money has been spent and UCSD has little to show for it. No research has been performed, at least eight people hired with the funds have been laid off and investigators are questioning whether the oncologist who solicited the gift — Dr. Kevin Murphy — misused the money for personal gain.

inewsource spent the past six months collecting thousands of pages of emails, legal documents, invoices and budgets to understand how one of the largest-ever donations for a UCSD employee’s research has been wasted. The answer grows more complicated the more we learn. It involves an entrepreneurial doctor using a novel technology and a university bureaucracy operating an alphabet soup of campus departments that try to enforce a seemingly endless set of rules.

Our reporting is the first public account to explain the complex events of the past five years and shines light on how a school that receives more than $1 billion in research funding from taxpayers each year handles its resources.

This story is difficult to unravel because the university won’t comment while the investigation continues, but we’ll tell you what we do know, and when the evidence is one-sided, we’ll point it out.

Kim Kennedy, UCSD’s chief marketing and communications officer, said the university will conduct a sit-down interview with us after the investigation is complete and share the findings.

Dr. Kevin Murphy, an oncologist and founder of Mindset and PeakLogic, sits for a photo at the UCSD Center for Neuromodulation on Dec. 6, 2019. (Brad Racino/inewsource)

Dr. Kevin Murphy, an oncologist and founder of Mindset and PeakLogic, sits for a photo at the UCSD Center for Neuromodulation on Dec. 6, 2019. (Brad Racino/inewsource)

We met with Murphy in his brain stimulation clinic for three interviews lasting more than 13 hours. The 52-year-old was defiant and eager to repair his reputation as the campus pariah. He was both haggard and energetic, answering our questions before we could finish asking them.

However, many of the things Murphy told us weren’t supported by evidence or we later found untrue. They included disparaging statements he made about one of his patients, a former Navy SEAL who had a psychotic episode after Murphy oversaw at least 234 brain stimulation treatments given to the veteran.

Murphy insists he’s done little wrong and that his critics are incompetent or jealous.

Hover over the text of this story to click the primary documents behind our article.

“I’m on the bleeding edge of this,” he said. “And so everyone’s shooting arrows in my back, going, ‘Stop him. Stop his research. Whistleblower him. We want this. Sue him. Make him look bad. Whatever it takes.’”

A $10 million gift is enough money that the president of the University of California system, Janet Napolitano, had to formally accept it. It’s enough money that UCSD referred to the gift as “transformational.” It’s enough money that a university doctor tried to build a research facility to validate his controversial technology.

But it wasn’t enough money to be worth it.

“I would give that $10 million back tomorrow and say it's not been worth the pain and the suffering,” Murphy said.

Chapter One: Brainpower

Kreutzkamp, a San Diego native, spent his adult life managing apartment complexes, passing time at his cattle ranch and raising exotic birds. He traveled the world in retirement with his wife, though that changed after his cancer diagnosis.

By the time the tumors had spread to his bones, the 72-year-old turned to Murphy. The doctor, a vice chairman for UCSD’s Department of Radiation Medicine and Applied Sciences, began treating Kreutzkamp around October 2014 at a private clinic in the northern San Diego neighborhood of 4S Ranch.

The building that houses California Cancer Associates for Research and Excellence (cCARE) in the neighborhood of 4S Ranch in northern San Diego is shown on Feb. 2, 2020. Dr. Kevin Murphy, a radiation oncologist at cCARE, also operates his personalized TMS clinic out of the building. (Zoë Meyers/inewsource)

The building that houses California Cancer Associates for Research and Excellence (cCARE) in the neighborhood of 4S Ranch in northern San Diego is shown on Feb. 2, 2020. Dr. Kevin Murphy, a radiation oncologist at cCARE, also operates his personalized TMS clinic out of the building. (Zoë Meyers/inewsource)

Within a few months, Kreutzkamp developed “chemobrain”: thinking and memory problems that can result from cancer treatment.

Murphy told us he decided to treat Kreutzkamp’s condition using his own form of transcranial magnetic stimulation, or TMS, which sends electromagnetic pulses into the brain. Experts can’t fully explain why it works, but TMS has often been described as a miracle treatment by people suffering from certain mental illnesses.

For instance, about half of patients with the hardest cases of depression — those who’ve tried medications without success — report a significant or complete reduction in their symptoms after four to six weeks of daily TMS treatment, though relapse sometimes occurs. That much improvement was virtually unimaginable for patients two decades ago unless they underwent a risky procedure now called “electroshock therapy.”

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration, which regulates drugs and medical devices, approved the first TMS machine for treating depressed patients 11 years ago. Since then, the federal agency has approved several more TMS devices to treat obsessive compulsive disorder and migraines, and hundreds of millions of dollars in government grants are paying for TMS studies on a multitude of conditions, including PTSD, anxiety, sleep and chronic pain.

TMS providers normally send electromagnetic pulses into all patients’ brains within standard rhythm and power settings. However, Murphy has a different approach. First, he takes a reading of each patient’s brainwaves using an electroencephalogram (EEG), then adjusts the TMS machine's settings to provide treatments tailored to their brains.

Murphy has trademarked his approach PrTMS, which stands for personalized repetitive TMS. He was eager to test his customized technique on his patients, including Kreutzkamp, before research showed it was effective.

The doctor insists his procedure works in treating a variety of conditions — including PTSD, autism, concussions, ADHD, depression, sleep disorders and anxiety — but four experts we spoke to think Murphy’s version of TMS is scientifically questionable.

After reviewing Murphy’s treatment, Simone Rossi, a world-renowned TMS researcher based out of Siena, Italy, said the doctor’s approach lacks “a solid neurophysiological basis.”

In our interviews, Murphy repeatedly made incorrect claims about the way traditional TMS works and unverifiable statements justifying why his modified version is superior. When we presented him with expert opinions contradicting his claims, he insisted that others don’t understand his technique.

“Know what we're doing first before you criticize it,” Murphy said.

Murphy described Kreutzkamp’s response to PrTMS as nothing short of extraordinary.

“He started to stand up and walk out of his wheelchair and mentate clearly,” Murphy said. “He's like, ‘This is crazy. How can I help you?’”

When Kreutzkamp died on Thanksgiving Day in 2015, he left an ambiguous letter from his family’s estate that would spark years of contention.

Depending on who you asked, the gift was either meant for Murphy to research PrTMS or for the UCSD Moores Cancer Center to study cancer treatments.

“The Trustee shall distribute the sum of Ten Million Dollars ($10,000,000) to the UC San Diego Foundation, located in San Diego, California, to be used for cancer research ...”

Murphy is adamant that the donation was clearly intended for him. He repeated the backstory so often that it adopted the veneer of a legend: One day, Kruetzkamp asked Murphy how much money the doctor would need to research the effectiveness of his treatment. Jokingly, Murphy said it would take $10 million. He estimated five trials focusing on different illnesses would cost $2 million a piece.

Murphy said he didn’t know his patient was wealthy, and he was stunned when Kreutzkamp told him he actually had the $10 million to give.

The story goes that even though Murphy treated Kreutzkamp at a private cancer clinic, he told his patient to donate the money to UCSD because it would be the easiest place to begin trials. Murphy said he then called a UCSD development office and told them a big donation, meant for him, was on its way.

Murphy said those early conversations were oral, and we haven’t been able to verify this story. However, emails show what happened once UCSD’s development office learned of the massive incoming gift.

In February 2016, a senior executive contacted the director of the Moores Cancer Center, Scott Lippman, to tell him the “good news” about the donation. The cancer center has run more than 200 clinical trials and employs more than 400 scientists, including a Nobel laureate and more than a dozen members of the National Academy of Sciences.

The Rebecca and John Moores UC San Diego Cancer Center is shown on Feb. 2, 2020. Dr. Kevin Murphy claims the cancer center tried to take funds from a $10 million donation that was intended for his research. (Zoë Meyers/inewsource)

The Rebecca and John Moores UC San Diego Cancer Center is shown on Feb. 2, 2020. Dr. Kevin Murphy claims the cancer center tried to take funds from a $10 million donation that was intended for his research. (Zoë Meyers/inewsource)

Murphy claimed that Lippman directed Moores officials to take the $10 million donation to fund their own projects, even though they knew the money didn’t belong to them. Lippman wouldn’t talk to us for this story.

“It turned into the cancer center saying, ‘Thank you, we'll take that off Dr. Murphy’s hands for him,’” Murphy said. “And then I had to extract a $10 million lollipop out of the cancer director’s mouth.”

Murphy tried to resolve the problem by approaching the dean of the School of Medicine at the time, David Brenner, who sits near the top of the campus hierarchy.

That same day, on March 31, 2016, the development office sent another email to Lippman about the donation.

In an email after the meeting with the dean, Murphy wrote that Brenner told him the donation would be “delivered to my research account in full.”

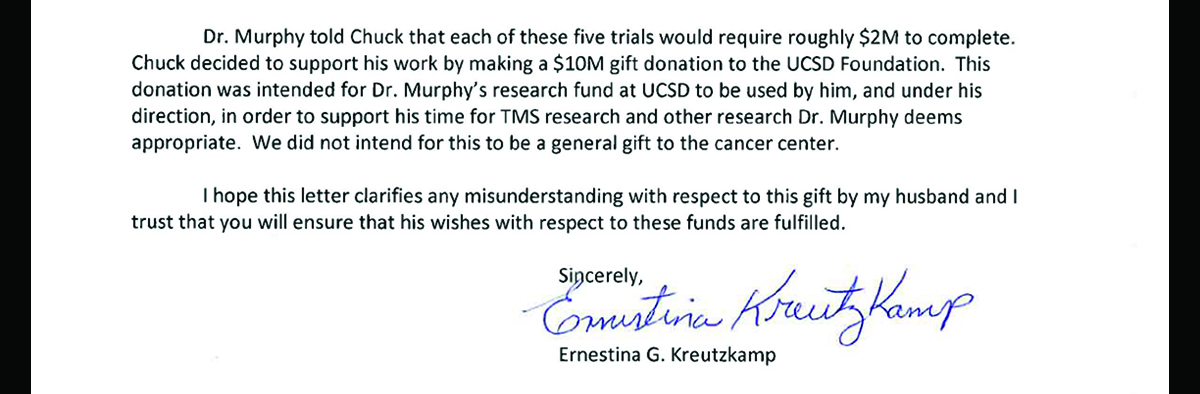

Months of email exchanges followed in which Murphy insisted the entire $10 million was his, and the dispute culminated in a signed June 2016 letter from Ernestina Kreutzkamp, Charles’ widow. She attested that her late husband was impressed by the wide range of people who walked in and out of Murphy’s clinic — including children with autism, military veterans and patients with cerebral palsy — and wanted to fund his work.

“We did not intend for this to be a general gift to the cancer center.”

(Worth noting: Ernestina Kreutzkamp’s letter was written in flawless English even though she speaks very little of the language. When we asked her lawyer about that, he was unsure who composed it.)

Part of the June 2, 2016, letter sent by Charles Kreutzkamp’s widow Ernestina to UCSD clarifying the intent of the $10 million donation. (Documents obtained from UC San Diego)

Part of the June 2, 2016, letter sent by Charles Kreutzkamp’s widow Ernestina to UCSD clarifying the intent of the $10 million donation. (Documents obtained from UC San Diego)

In January 2017, the attorney for the Kreutzkamp family and president of their foundation, Robert Pizzuto, went to the dean’s office to present a check to UCSD. In Murphy’s retelling, the lawyer angrily snapped the check in Brenner’s face to insist the money would end up in Murphy’s hands. Pizzuto denies the check-snapping and said he was unaware of Murphy’s claims about the money being redirected to the cancer center. Brenner wouldn’t comment.

Pizzuto said he believed Kreutzkamp always wanted the money to go to Murphy but never relayed that explicitly. The language in the trust was ambiguous, he said, because the philanthropist’s health went sideways before he could fine tune it.

“Those are my words in that trust as relayed through Mr. Kreutzkamp,” Pizzuto said.

Murphy said campus officials have held a vendetta against him ever since he wrenched the money from the university.

“I created an enormous enemy and became persona non grata at the university amongst these upper echelons because I was the bastard who stole the $10 million back,” Murphy said.

Chapter Two: Vested interests

Murphy believes he brings something special to TMS because of his background treating the brains of children with cancer: He isn’t afraid to try the technology on a wider range of physical and mental problems, including chemobrain.

The oncologist put his first TMS machine in his cancer center and offered the treatment to his cancer patients, then expanded to include those with PTSD, cerebral palsy, autism, Alzheimer’s disease and other disorders. After seeing how much they improved, he said, he started working out of a private clinic in Del Mar devoted to personalized TMS.

A part of a Magventure TMS machine that allows the treatment to be customized is shown in the UCSD Center for Neuromodulation on Dec. 6, 2019. (Brad Racino/inewsource)

A part of a Magventure TMS machine that allows the treatment to be customized is shown in the UCSD Center for Neuromodulation on Dec. 6, 2019. (Brad Racino/inewsource)

UCSD employees must follow a cascade of rules when starting a private business to make sure their new venture doesn’t interfere with their university obligations. The employees are required to keep track of how much time they spend on the business, report the income they earn from it and work with the school if they want to patent an invention.

While navigating that process, Murphy established a relationship with a top university lawyer: Mike McDermott, chief counsel of the university health system. The attorney’s job was to defend the school against malpractice lawsuits and give campus health officials legal advice.

McDermott was also involved in several of Murphy’s enterprises.

By looking through California business filings, we found that the attorney served as a corporate officer for one of Murphy’s nonprofits; served as the chief financial officer for a Murphy company called FreqLogic, which aimed to build a prototype for a small, easily portable TMS machine; and managed a business called TMSC Services LLC, which contracted to hire personnel, maintain equipment and oversee the clinic’s finances in exchange for 15% of its revenue.

The university provided us with McDermott’s annual disclosures, which show the attorney never listed those business interests during his two-year tenure. UCSD wouldn’t tell us how much they knew — if anything — about McDermott’s financial relationship with a faculty member he was advising.

When investigators later scrutinized whether Murphy followed university rules while running his private businesses, McDermott became a frequently cited excuse: Murphy was working with a university lawyer as he opened and grew his businesses, so he figured he had UCSD’s approval.

As for whether McDermott should have been working for Murphy’s side businesses, Murphy told us he had no reason to second-guess the actions of a distinguished attorney.

In June 2016, McDermott left UCSD to work with Murphy full time.

“He was seeing what everyone tends to see: ‘Oh my God, you're not kidding. You're making autism kids speak.’” Murphy said. “‘I have seen it happen now.’ And once he heard the veterans’ stories and the testimonials he started saying, ‘I want to manage your organization.’”

It didn’t last long. In April 2017, Murphy terminated McDermott’s contract. The attorney stepped down from his roles in Murphy’s other businesses, then left California.

It took us days to track down McDermott to ask what happened. We finally found him in Long Island, New York.

“I’m not interested in talking about UCSD,” he said, and then hung up the phone.

Murphy’s wife Lisa, a chief administrator at UC San Diego Health, also helped out with her husband’s private businesses.

She sent estimated revenues and expenses to investors interested in taking over two of Murphy’s personalized TMS clinics in Indiana, and she was included in an email breaking down costs for someone in another state who wanted to use Murphy’s treatment. The price: $50,000 plus an additional $10,000 per patient on average. The email said clinics could expect to charge their patients $20,000 for a course of PrTMS.

Lisa Murphy is also listed in corporate filings as the president of PeakMD, a nonprofit her husband set up to accept donations meant for veterans to receive his treatment. She told us she was included in those filings by mistake and never worked for Murphy’s personalized TMS companies.

Chapter Three: Mixed messages

As Murphy ramped up his private businesses and publicly funded research, the two began to blur.

By early 2017, Murphy had wrangled the $10 million for research but was still more than a year away from beginning it. His goal was to conduct five experiments simultaneously, focusing on different illnesses. That’s a hefty undertaking even for someone with experience leading trials, and Murphy had very little.

So he made a decision that he thought would ease the process, not knowing how much scrutiny he’d later face for it.

Until that point Murphy had relied on trial and error to customize PrTMS. After reviewing his patients’ EEGs, he offered them treatments based on his own judgment on a case-by-case basis.

Murphy wanted to build an algorithm that could do the work for him, so he founded the company PeakLogic to create software that would read brainwaves and recommend treatment plans without needing the doctor’s input.

The software had two potential benefits. First, it would replace Murphy’s judgment calls with a completely neutral computer algorithm, which you need for an impartial clinical trial. Second, it could be patented and sold for a profit.

Contact the reporter

Do you have information that could further inewsource’s investigation that you’d like to share with reporters?

Contact Jill Castellano:

[email protected]UCSD employees often invent new technologies, and when they do, they are supposed to sort out the legal details with the campus patent office known as Tech Transfer. The office decides who owns the intellectual property and whether employees can earn money off of their inventions.

The process aims to avoid conflicts of interest, where employees might be torn between doing what’s best for their personal finances and what’s best for the public institution that funds their salaries through taxpayer dollars.

But Murphy didn’t consult with the patent office before founding PeakLogic, and without that clear pathway forward the doctor’s relationship with UCSD drifted into undefined territory.

In the coming years, without advanced approval from the patent office, Murphy used university time, staff, office space and the $10 million donation in a way that could have enriched himself and his private companies.

That’s why he’s currently under investigation.

Murphy spent millions of dollars from the Kreutzkamp gift to pay for research that could prove (or disprove) his software’s effectiveness in treating a host of mental and physical disorders. With rigorous scientific evidence backing up his personalized TMS, PeakLogic could become attractive to investors, clinics and patients around the country and earn the doctor a big payday.

Murphy told us he had UCSD’s blessing to create PeakLogic, and he properly disclosed his private businesses on university forms. However, he shifted parts of his story after we checked out his statements.

For example, Murphy said Eric Mah, a UCSD administrator responsible for clinical research operations, knew all along about the doctor’s intention to create the software. In fact, Mah was the person who suggested creating it, Murphy said.

In 2017, PeakLogic paid a healthcare software company in Bozeman, Montana, to start building an algorithm. In the meantime, Murphy was trying to get his research off the ground.

He opened UCSD’s Center for Neuromodulation, a research lab with 5,750 square feet of space to pursue all of his personalized TMS projects. It’s 15 miles northeast of campus but in the same building as Murphy’s private PrTMS clinic, which had moved from Del Mar to 4S Ranch.

A map showing the UCSD Center for Neuromodulation’s layout hangs in one of its offices on Dec. 6, 2019. (Brad Racino/inewsource)

A map showing the UCSD Center for Neuromodulation’s layout hangs in one of its offices on Dec. 6, 2019. (Brad Racino/inewsource)

Murphy drew more than $700,000 from the Kreutzkamp fund to pay himself and at least seven people to work at the center beginning in 2017. He spent another million dollars on 19 brain stimulation machines. (A sales executive working for the international company that manufactures the machines told us Murphy is one of its largest customers.)

UCSD assigned one part-time staff member in Murphy’s department to oversee the $10 million, rather than providing a full-time manager based out of the dean’s office. Murphy said that wasn’t nearly enough support to keep track of his projects.

“Once I pissed off the cancer center, I was like an enemy at that point because I'd taken the money,” Murphy said. “I didn't have a leadership team to go through and say, ‘Help me get this done.’”

Murphy asked Diana Shapiro to assist. Today, Shapiro manages PeakLogic’s business operations and creates licensing agreements for other clinics offering PrTMS — currently 13 offices in 10 states. Back then, she was a volunteer helping Murphy start the business.

Murphy wanted Shapiro to take on a consulting job at UCSD to help manage the research projects, though she had no experience in clinical trials. She was hired on a $7,000 monthly contract, which was later bumped up to $10,000.

Shapiro is a longtime corporate sales executive who said she met Murphy while picking up takeout sushi. Murphy overheard Shapiro talking about a relative’s problems and the doctor recommended she bring the person to his clinic, now called Mindset. Shapiro said she was shocked by how much the treatment improved the relative’s sleep and anxiety.

“That's why I work here,” Shapiro said. “First as a volunteer to help give back to someone who's giving to the community. But then with my background in business, I just looked at him like, ‘We need to scale this. We need to give this to the world.’”

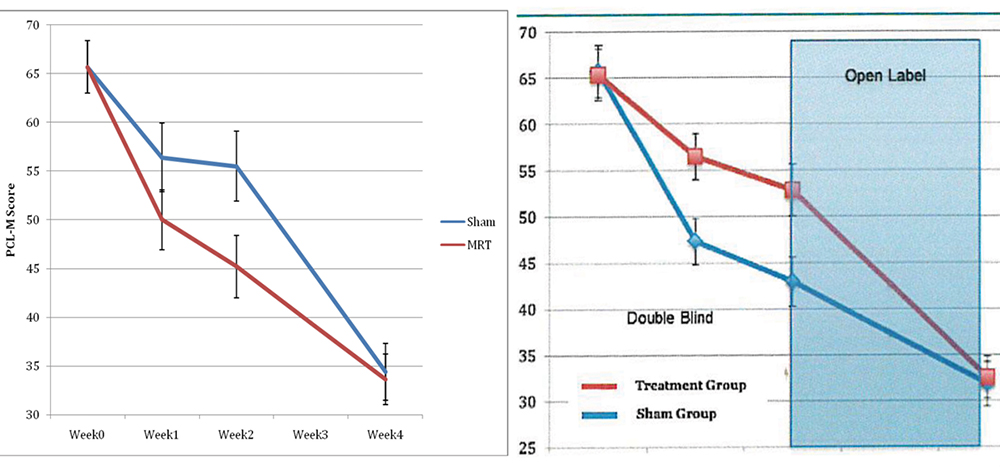

Dr. Kevin Murphy is shown in this photo illustration. (Ruth Crowe for inewsource)

Dr. Kevin Murphy is shown in this photo illustration. (Ruth Crowe for inewsource)

Emails and budgets reveal that Shapiro wasn’t the only person with dual roles. Murphy used the Kreutzkamp donation to pay his brother Mike Murphy, a chiropractor, as a UCSD clinical trials coordinator on a $72,000 salary. During that time, his brother was the corporate secretary of PeakLogic and assisting Murphy at his private clinics.

Murphy told us that he helped his brother get the job at UCSD because of the chiropractor's “special knowledge” in reading EEGs, which Murphy taught him to do in prior years.

“I was giving him a place to go,” Murphy said. “He had no job. He was helping me. He was, I think, uniquely qualified to do EEG analysis with me. He was learning with me. I was teaching him.”

In June 2018, a member of Murphy’s department filed a whistleblower complaint with UCSD claiming that Murphy’s brother and colleague were hired under false pretenses and that they didn’t have the skills required for the jobs. The employee — who we are keeping confidential to protect from retaliation — alleged Mike Murphy and Shapiro spent their publicly paid time working for PeakLogic: Mike Murphy was trying to write the company’s software code and Shapiro was helping the business grow.

Murphy forcefully denies the accusations. He said he and his employees wear different “hats” depending on which office they’re in. When they walk into the Center for Neuromodulation, they are supposed to assist with UCSD research and get paid through the $10 million Kreutzkamp fund. When they exit, turn left 90 degrees and walk into the Mindset clinic, they treat patients, build algorithms or sell software licenses, and are paid by Murphy’s private companies.

Murphy said that his brother had mistakenly told people he was working on PeakLogic’s algorithm, which led to confusion about Mike Murphy’s role at UCSD.

“I get upset by it because my own brother has been such a thorn in my side who I have done so much for,” Murphy said. “And his comments that he may have said to somebody have led to so many questions that are not relevant.”

Mike Murphy didn’t respond to our interview requests.

Shapiro said she was qualified for the UCSD job and followed all university rules.

“We went through all the proper channels to get me hired so that I could help him with this process,” she said.

Records also show Murphy asked the university to cut him a check for more than $16,000 from the Kreutzkamp fund to pay an employee at his private clinic who did not work for UCSD. Murphy told us it was to reimburse the employee for furniture she purchased for his UCSD research lab.

As part of the internal investigation, auditors obtained an inventory of equipment costing more than a quarter million dollars that’s alleged to be missing from UCSD, including 15 laptops and 14 EEG headsets, as well as three TMS machines worth a total of $170,000 purchased using the Kreutzkamp donation.

The doctor explained to us that there were some equipment mixups at one point, because he was purchasing machines for his public lab at the same time he was buying identical equipment for his private clinic next door. The machines were all delivered in boxes and kept in a single pile, he said, causing some equipment with UCSD serial numbers to end up in the wrong place. He said all the issues have been resolved and nothing is missing.

“I'm going to fall on the sword and say I've not been probably as good as I'm going to have to be going forward in inventorying and auditing things,” he said. “Because most doctors don't do that. We go see patients, and we work on other stuff.

“We're not looking at serial numbers on boxes and stuff.”

Chapter Four: Limbo

Ethical human experiments in the U.S. need advanced approval from institutional review boards, which read proposed studies carefully and ensure participants will be protected from harm. Big research centers like UCSD have a handful of them.

In August 2016, Murphy brought his first PrTMS trial to a UCSD review board. It wasn’t approved. He wanted to study the treatment on kids and adults with neurodevelopmental disorders, including autism and cerebral palsy. The board said Murphy didn’t provide evidence his research would be safe for children, pointing out that the FDA has approved TMS devices only for patients ages 22 and older.

Over the next two years, Kreutzkamp-funded research proposals multiplied and morphed, according to documents Murphy gave us during our interviews.

Murphy said UCSD officials told him that a review board wouldn’t approve a study using his own technology if he was overseeing the research — that would create a conflict, since he has a financial interest in the research’s success — so he asked others to take the lead. He found UCSD doctors and scientists, convinced them to perform trials on PrTMS and offered them money, office space and equipment.

The UC San Diego Jacobs Medical Center, a teaching hospital on the university’s campus, is shown on Feb. 2, 2020. (Zoë Meyers/inewsource)

The UC San Diego Jacobs Medical Center, a teaching hospital on the university’s campus, is shown on Feb. 2, 2020. (Zoë Meyers/inewsource)

Employees within a UCSD campus neuroscience lab and an engineering school took the offer, as did a doctor at Rady Children’s Hospital. Murphy was ready to fund trials on patients with chemobrain, opioid addiction, concussions, autism, PTSD and cerebral palsy.

However, most of the studies fizzled out before they began, and the one that made it past the approval process was shut down.

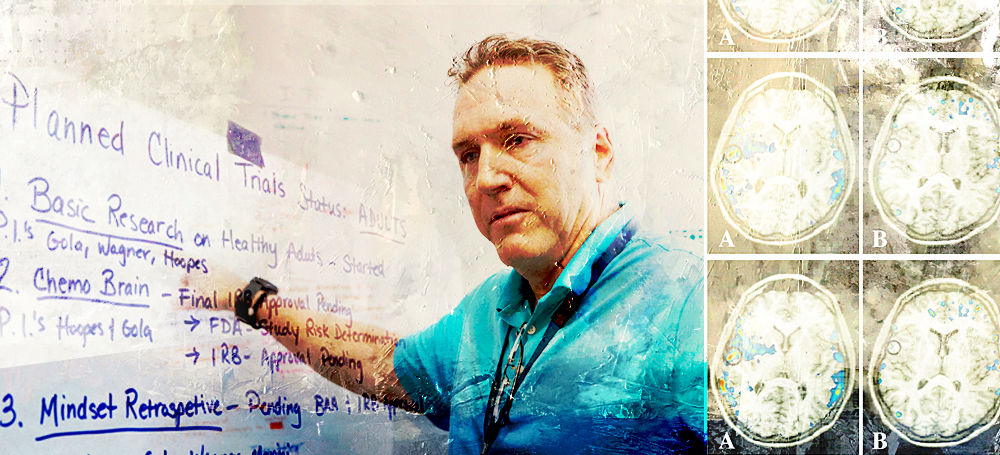

For PTSD, Murphy wanted to partner with the San Diego VA for a trial on veterans. In the research proposal, which he provided to us, he included a description and graphs from a “preliminary study” where 36 combat veterans who received PrTMS saw a 65% drop in their trauma symptoms after treatment. But Murphy never performed that study — a competitor offering its own version of customized TMS did. Murphy’s language and charts were almost identical to the originals, except the name of the competitor’s technology was swapped out for Murphy’s “PrTMS.”

We asked the competitor, Newport Brain Research Laboratory, to review the similarities we found. A spokesman said that “to our amazement, (we) can confirm that they are from a Newport study.”

An ethics expert and associate vice provost for research development at Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine, Dr. Harold Garner, reviewed both Murphy’s VA proposal and the original study it was taken from.

He told us, “This is what would be considered by scientific professionals to be plagiarized material.”

(You can read Murphy’s complicated explanation for this here.)

Dr. Kevin Murphy’s proposal to test PrTMS on veterans with PTSD (right) took language from a previous study performed by his competitors (left) and substituted the word “PrTMS” in place of “MRT.” (Document courtesy of Kevin Murphy and Newport Brain Research Laboratory)

Dr. Kevin Murphy’s proposal to test PrTMS on veterans with PTSD (right) took language from a previous study performed by his competitors (left) and substituted the word “PrTMS” in place of “MRT.” (Document courtesy of Kevin Murphy and Newport Brain Research Laboratory)

Murphy’s PTSD trial with the San Diego VA never got started. After a year of work, the doctor stopped responding to emails and phone calls from his VA partners because, he explained to us, they were trying to overcharge him.

For Murphy’s trial on cerebral palsy, the doctor struck up a relationship with Andrew Skalsky, a psychiatrist at Rady Children’s Hospital. When Skalsky submitted a proposal for a PrTMS study, the review board initially didn’t approve the idea. They asked Skalsky to explain Murphy’s role in the research and how the study was funded, and they wanted him to obtain an FDA device exemption before beginning the research.

Skalsky eventually got signoff from the review board and the FDA, but a research agreement between UCSD and the hospital was never executed, so the study didn’t progress.

For chemobrain, Murphy collaborated with the Swartz Center for Computational Neuroscience, a UCSD lab specializing in exploring dynamic connections between human brain regions. The lab’s researchers agreed to test PrTMS on chemobrain patients, but asked Murphy to fund something else, too — basic research to examine what factors make standard TMS less or more effective. The Kreutzkamp donation funded both.

By late 2017, the Swartz team carrying out the experiments included a clinical psychologist as a research manager, two post-docs, a senior member of the neuroscience lab, two graduate students, a technician, a research assistant and a nurse. The center’s director, Scott Makeig, was in charge of the basic research project, while two other senior lab members oversaw the chemobrain trial and the research’s engineering needs. The team drew more than half a million dollars from the Kreutzkamp fund to cover their salaries and benefits.

The university’s clinical trials office suspended the basic research project in December 2018 after notifying Makeig that it had concerns about Murphy’s “interests” in the research that hadn’t been disclosed to the board.

Murphy contacted the chair and vice chair of his department, the dean’s office and the campus ombudswoman but couldn’t resolve the problem. He told Makeig he was going to pull the lab’s funding.

Murphy withdrew the funding anyway. The Swartz Center terminated the first members of the research team in early February 2019, citing “budgetary restrictions.”

The employees laid off included an assistant research professor on a work visa, two post-doctoral workers who were supposed to have a yearlong appointment and two research assistants, one of whom was pregnant with her first child. The five of them had been paid a total of $325,000 from the Kreutzkamp donation before they were let go.

After filing complaints through their unions, the post-docs were reassigned to other projects and the pregnant employee was allowed to remain on staff until her maternity leave ended. The other research assistant lived on unemployment benefits for two months until she found a job in a different UCSD department.

The Biomedical Sciences building at UC San Diego's School of Medicine is shown on Feb. 2, 2020. Dr. Kevin Murphy, who served as vice chair for UCSD's radiation department, is now at the center of an investigation into how a $10 million donation to the university has been spent. (Zoë Meyers/inewsource)

The Biomedical Sciences building at UC San Diego's School of Medicine is shown on Feb. 2, 2020. Dr. Kevin Murphy, who served as vice chair for UCSD's radiation department, is now at the center of an investigation into how a $10 million donation to the university has been spent. (Zoë Meyers/inewsource)

The assistant research professor struggled for months to keep his immigration status but was eventually offered a half-time position in Makeig’s lab in the Swartz Center.

Murphy told us he agreed to pay for Makeig’s general study on how TMS works under the assumption that the neuroscience lab would be conducting the chemobrain study — using his company’s software — at the same time. Because the chemobrain project was on hold, Murphy felt he wasn’t honoring the “donor’s intent” by giving Makeig money.

Murphy said if the employees who filed complaints are mad at him, they’re “blaming the wrong person.” He contends the people who suspended his research are ultimately responsible for the terminations.

Undeterred by the internal investigation, Murphy is now pursuing two research projects on his customized TMS outside the university.

One is a retrospective study using data Murphy has already collected on his patients, paid for by PeakLogic. The other, funded by the U.S. Special Operations Command, will test how PrTMS affects human performance and improves “symptoms experienced by military personnel who suffer from chronic pain,” according to a SOCOM spokesman.

UCSD policy requires its faculty and staff to get approval from the university when conducting outside research, but Murphy never went through that process for either project.

Murphy said that’s because his private company is conducting the research, but UCSD makes it clear that its policy still applies.

“Couldn’t care less,” Murphy told us.

“Why would I go to those clowns again?”

Chapter Five: Due process

The investigation into Murphy and the $10 million donation has lasted a year and a half. The university won’t provide us with documents or information about it while it’s ongoing. What we do know has been obtained from other sources.

Two partners at one of the most famous law firms in the U.S. are helping the UC Office of the President, which is based out of Oakland, conduct the internal investigation. Boies Schiller Flexner has been in the news for allegedly intimidating whistleblowers who spoke up about fraud at the billion-dollar company Theranos, and one of the firm's lawyers is known for representing the Vice President in Bush v. Gore.

In the past year, investigators have interviewed Murphy’s wife, colleagues and staff members, as well as the doctor himself. A second group, made up of UCSD auditors, has been gathering information on how the $10 million was spent.

The UC San Diego School of Medicine campus is shown on Feb. 2, 2020. Dr. Kevin Murphy, who served as vice chair for UCSD's radiation department, is now at the center of an investigation into a $10 million donation to the university. (Zoë Meyers/inewsource)

The UC San Diego School of Medicine campus is shown on Feb. 2, 2020. Dr. Kevin Murphy, who served as vice chair for UCSD's radiation department, is now at the center of an investigation into a $10 million donation to the university. (Zoë Meyers/inewsource)

Around August 2018, the auditors contacted clinics that were offering Murphy’s treatment to ask them questions and told them Murphy was under investigation.

“I was fuming,” Murphy told us in an interview, still furious that the auditors didn’t talk to him first before reaching out to his business clients.

“Come over and do your own audit here,” he said. “I'll give you everything you want to look at, open kimono. I'm a doctor and a vice chair of a department. I'm going to be selling in the black market, some of your EEG caps or something, to make an extra grand? Uh no.”

He sent the auditors a long email, accusing them of harming his business and insisting they stop.

In the year after the investigation began, Murphy was still drawing $213,000 in salary and benefits from the Kreutzkamp donation, in addition to $80,000 from his software company and $30,000 from his personalized TMS clinic. (Murphy said the $213,000 replaced the salary he was previously earning from other UCSD funds.) His office manager was earning $184,000 from the Kreutzkamp fund, though there were no ongoing studies to manage.

Murphy told us that during that time, he was trying to find a solution at UCSD that would restore his research efforts.

An official in the dean’s office informed the doctor in late 2018 that transitioning to a part-time employment status “would alleviate the conflict of commitment issues,” and Murphy’s boss told him the change “will be helpful in getting your trials going again,” emails show.

However, according to Murphy, a former campus compliance officer, Dan Weissburg, told the doctor’s boss not to sign off on the employment change.

When Weissburg found out about the complaint, he allegedly threatened Murphy over the phone, telling him “this may not work out for you to stay here at UCSD” and “other, more serious committees would now need to get involved” in the internal investigation. This account comes from notes Murphy said he wrote after the conversation occurred, but we have no way of verifying their authenticity.

(Weissburg was a key figure in our investigation into UCSD’s decision not to tell HIV-positive women their confidential data was breached.)

Weissburg, who no longer works at UCSD, said he didn’t threaten Murphy and only learned about the whistleblower complaint in the past month. (You can read his full statement here.)

Murphy claimed his boss — radiation department Chairman Arno Mundt — was on the phone when the compliance officer threatened him, but Mundt didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Murphy was eventually allowed to become a part-time employee but made his frustrations clear in an email to Mundt accepting the new position, describing the ongoing scrutiny into his work as an “Inquisition” led by Weissburg.

Medical Center Drive, where the UCSD Moores Cancer Center is located, is shown on Feb. 2, 2020. Dr. Kevin Murphy claims the cancer center tried to take funds from a $10 million donation that was intended for his research. (Zoë Meyers/inewsource)

Medical Center Drive, where the UCSD Moores Cancer Center is located, is shown on Feb. 2, 2020. Dr. Kevin Murphy claims the cancer center tried to take funds from a $10 million donation that was intended for his research. (Zoë Meyers/inewsource)

When we called Kreutzkamp’s widow in November to ask her about the audits and investigation, she gasped. Nobody had told her about the chaos her family’s donation had caused.

“We have a foundation, and in the future we would like to leave more money for UCSD,” Ernestina Kreutzkamp said in Spanish. “But if this is happening, we would like to clear this misuse before then.”

Pizzuto, the attorney for the Kreutzkamp family who helped shepherd the $10 million to UCSD, also wasn’t told about the internal investigation, he said. Ernestina Kreutzkamp and Pizzuto have requested documents from the university to understand how the donation has been spent.

“I’m just sorry it’s come to this…,” Pizzuto told us at his downtown San Diego office in January. “I just hoped that the money would be given, the research would be done, good would come from the research and society would benefit. I’m sure that’s exactly how Mrs. Kreutzkamp feels, too.”

At UCSD, Murphy has accused more than a dozen people involved in the $10 million donation of making critical mistakes, sabotaging him or wanting him to fail. Nearly everyone at the university we reached out to about Murphy declined to comment on the record because of the continuing investigation.

Murphy hasn’t gotten three expected bonuses from the university, he said, and his biography was removed from its website. His lawyer sent Boies Schiller Flexner investigators a cease and desist letter, demanding they stop Murphy’s boss from spreading rumors about him. He invoiced the university for $75,000 in legal fees he has spent defending himself against his employer.

The university hasn’t paid him back.

Murphy has contacted department leaders, the research compliance office, the auditors, the investigators, the communications office, the patent office, leading UCSD attorneys and the school foundation that accepted the $10 million. He’s been repeatedly told they can’t speak to him while the investigation is ongoing, he said.

"There's no due process,” Murphy told us. “Eighteen months go by. No one's told me a thing. No one's said, ‘Here's where you stand. Here's what you're being accused of.’ You're guilty until proven innocent versus innocent until proven guilty. It's like, you must have done something wrong. They clearly haven't found anything.”

Meanwhile, what remains of the Kreutzkamp family donation is still in a bank account, burning more than $22,000 a month to rent a dark, locked research lab that Murphy has called one of the “largest neuromodulation centers in the world.”

Clarification: Feb. 13, 2020

The references to Diana Shapiro’s relative, who was treated by Dr. Kevin Murphy, have been updated in the story.