The Navy SEAL and His Doctor: An experimental brain treatment blows up two lives

By Brad Racino and Jill Castellano

Feb. 12, 2020

When Johnathan Surmont checked himself into the San Diego VA psych ward in the summer of 2017, the tall, clean-cut veteran removed his sandals and absolved the medical staff of all sin.

He was God’s second son, he announced, and he couldn’t wait for karaoke night.

Surmont’s psychotic episode continued after his release from the VA, and it took the 45-year-old former Navy SEAL on a weeks-long breaking, entering and vandalizing tour from San Diego to Los Angeles. During that trip, he went far off the grid: ditching his phone, forgetting his own name and believing he was part of a covert military operation where all things in his path — coins, car maneuvers, airplanes, even arresting officers — cued him toward his next steps.

As a Navy SEAL, he was a highly trained military weapon capable of harming a large number of people, so family and friends breathed easier when the father of three resurfaced weeks later as an inmate at an L.A. County jail, calling himself John Francis Kennedy.

Surmont struggled with post-traumatic stress after tours in the Middle East and Asia. A car accident in 2013 worsened and compounded that condition by adding to it a traumatic brain injury. But more than 100 medical checkups and psychological evaluations showed he had no history of psychosis, mania, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia or hallucinations leading up to the onset of his symptoms in early 2017.

VA doctors were stumped when his psychosis fizzled following his incarceration, never to reappear. They noted in Surmont’s medical record that determining the cause was unimportant — an “academic exercise.” But the doctors had a hunch. So did Surmont. So did his family and friends. So did his psychologist and his psychotherapist girlfriend.

It involved Dr. Kevin Murphy, an oncologist and vice chairman in the school of medicine at the University of California San Diego. Medical records show it was Murphy who supervised at least 234 treatments of an unproven type of electromagnetic therapy to Surmont’s brain in the years leading up to the psychotic break.

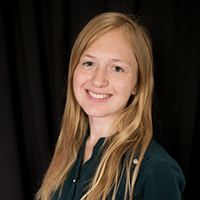

Kevin Murphy is pictured with his arm around John Surmont during a trip to Utah in this undated photo. (Courtesy of John Surmont)

Kevin Murphy is pictured with his arm around John Surmont during a trip to Utah in this undated photo. (Courtesy of John Surmont)

Transcranial magnetic stimulation is a relatively new medical treatment that uses electromagnetism to change the brain’s neural networks. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved TMS machines to treat major depressive disorder, migraines and obsessive-compulsive disorder, and the therapy is rigorously studied — with published scientific research proving its safety and effectiveness.

Though Murphy’s career has focused on cancer care for more than a decade, after six years of working with TMS, he now considers himself a pioneer in that field. The doctor states proudly and often that his version of “personalizing” TMS surpasses all others, yet there is no clinical trial or published research supporting that claim.

“I would stand on a stage right now in front of the entire academic community and say, ‘What we're doing is better,’" Murphy told inewsource in a November interview.

Murphy calls his secret formula PrTMS, which stands for personalized repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation. Over the past six years, he said, he has used it to treat around 5,000 patients suffering from autism, cerebral palsy, concussion, depression, anxiety, ADHD, PTSD, sleep disorders and a bad golf swing — all to great results.

inewsource spent more than 13 hours interviewing Murphy over several days to understand his history with Surmont and the basis behind his sweeping statements regarding PrTMS. In the end much of what he said crumbled when confronted by facts.

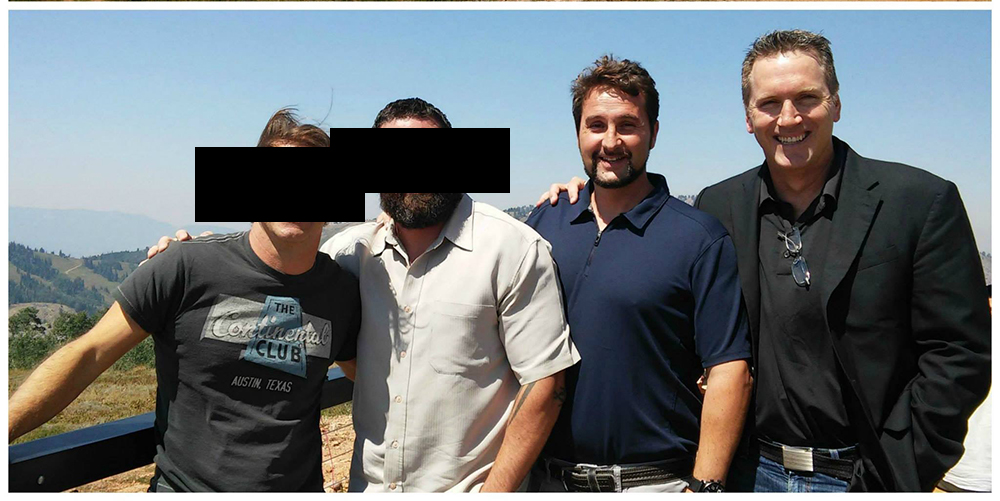

Dr. Kevin Murphy, an oncologist and founder of Mindset and PeakLogic, sits for a photo at the UCSD Center for Neuromodulation on Dec. 6, 2019. (Brad Racino/inewsource)

Dr. Kevin Murphy, an oncologist and founder of Mindset and PeakLogic, sits for a photo at the UCSD Center for Neuromodulation on Dec. 6, 2019. (Brad Racino/inewsource)

It turns out PrTMS’s great results are based on Murphy’s opinion and inaccurate scientific benchmarks, not on the outcome of professional research.

Also, his repeated claims to veterans, nonprofit groups and the public about performing research on PrTMS are not true. The doctor told inewsource he has never conducted trials on PrTMS and chalked up his previous claims to being too liberal with the word “research.”

“It’s clearly the same mistake I made over and over again,” he said.

Additionally, inewsource discovered Murphy plagiarized a competitor’s data to justify beginning human research trials at UCSD and the San Diego VA.

Yet there is no doubt people believe in PrTMS. The former vice admiral and surgeon general of the U.S. Navy, Harold Koenig, provided the doctor with a testimonial, and patients throughout 10 states pay thousands of dollars for it in clinics that license with Murphy’s company.

Also, the U.S. Special Operations Command, which oversees special operations in the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, and Air Force, is expected to soon begin testing Murphy’s treatment on military personnel to examine its effects on “human performance.”

Even Surmont, who filed a complaint with the California Medical Board against Murphy in early 2019, believes the doctor’s personalized treatment is a “Nobel Peace Prize therapy” if done right.

“If it's not done right, it's a fucking weapon that's going to harm people,” he told inewsource.

John Surmont is shown on a vessel in the South China Sea while serving with SEAL Team 3 Golf Platoon in this undated photo. (Courtesy of John Surmont)

John Surmont is shown on a vessel in the South China Sea while serving with SEAL Team 3 Golf Platoon in this undated photo. (Courtesy of John Surmont)

Surmont, who refers to himself as Murphy’s “patient zero,” spent the past six months speaking with inewsource. Reporters followed him to court appearances, family outings and dog parks, and accompanied the veteran to L.A. to retrace his steps from his psychotic break two years ago. Surmont also gave reporters access to his medical history, arrest reports, court records, friends, family and colleagues.

He isn’t seeking money or retribution. He said he wants his doctor to admit what he has done, learn from it and move on.

“He pushed me too far,” Surmont said. “He pushed me over the edge into the abyss.”

Murphy disagrees, and warned inewsource against trusting his patient.

“Just know that you’re picking a psychotic for your information,” Murphy said, adding that he wasn’t responsible for the Navy SEAL’s breakdown because he hadn’t seen or treated the veteran in six months leading up to it. Plus, he said, Surmont had a history of mania.

When confronted with Surmont’s medical records, which reveal Murphy had in fact treated the veteran 65 times during those six months and that Surmont had no history of mania, Murphy said it was possible PrTMS could be responsible, but not likely.

“The John Surmont story is one out of 5,000 people, right?” Murphy said. “I actually looked it up: It's more likely to be hit by lightning — one in 3,000 lifetime chance — than it is to have a psychotic episode from our treatment.”

Murphy is fed up and not only with the Navy SEAL.

A whistleblower complaint in June 2018 prompted the University of California Office of the President to investigate the doctor’s alleged misuse of a $10 million research donation. A gift that size meant UC President Janet Napolitano had to formally accept it.

UCSD suspended Murphy’s PrTMS research due to conflict of interest concerns and not one patient has been treated in his lab. Yet Murphy has still managed to spend more than half of the $10 million gift. The university isn’t answering Murphy’s questions and his boss won’t speak to him, he said.

Outside academia, two lawsuits against Murphy claiming fraud, deceit and slander have cost the doctor time, money and clients.

Murphy even made enemies with San Diego native David Wells, one of Major League Baseball’s greatest left-handed pitchers. Wells donated $100,000 in 2018 to a veteran-focused nonprofit Murphy established but told inewsource he’d never give the doctor another penny after Murphy then repeatedly blew off Wells’ invitations to speak at his events.

“I’m being attacked on so many levels here,” Murphy said.

inewsource contacted more than 40 people affected by the doctor’s and veteran’s actions. Reporters read thousands of pages of university and medical records, lawsuits, arrest reports, research proposals, emails and leaked documents to put together a comprehensive picture of a nearly unbelievable story. They also interviewed TMS experts around the world to better understand the emerging therapy and get their take on physicians such as Murphy who are marketing it as the newest panacea in medicine.

The result is a narrative about two remarkably similar men: Both are veterans and fathers who discovered TMS out of desperation, formed a mutually beneficial alliance, suffered when their names were sullied, then turned against each other and the rest of the world as they fought to clear their names.

This is a story about a new therapy that could help millions of the most afflicted and vulnerable people around the world, if tested rigorously and honestly. Along with a companion piece here, it is also the first published account of an ongoing University of California investigation into how one of the largest-ever research donations for a UCSD employee was wasted.

It is a tale about what can happen when the line between hard science and anecdotal success becomes blurred, when big egos clash with big money and when doctors alter the brainwaves of some of the most dangerous men on the planet.

Chapter One: Sunshine helps

Johnathan Steven Surmont’s earliest memories are of his mother singing to him.

Homeless, she’d shuffle him and his brothers around the country in the 1970s, once cooking Christmas dinner on a hot plate in a Greyhound bus station bathroom stall. A backdrop of shoes, pants and knees were as close as the family would get to stockings on a fireplace. The boy had no idea his life was different from anyone else’s.

“I thought everybody was looking for food and shelter and safety,” Surmont said.

Law enforcement discovered the 6-year-old and his mother sleeping under a car and eventually placed him in foster care, where he said he suffered sexual abuse from other children. He never saw his mother again. The Surmont family from Corbin, Kentucky, took him in after three years in the system and provided a new surname.

A drawing made by John Surmont for social workers in 1979 is shown in this photo taken on Dec. 19, 2019. (Zoë Meyers/inewsource)

A drawing made by John Surmont for social workers in 1979 is shown in this photo taken on Dec. 19, 2019. (Zoë Meyers/inewsource)

Normalcy came. Surmont played sports and tried his hand at acting and broadcasting. He enrolled at the University of Kentucky but struggled with feelings of disconnection and angst. He dropped out of college and joined the Navy in 1991. At first, he was a cook.

“They always need somebody to flip a hamburger on a frigate,” he said.

But when an opportunity came early on to join the SEALs, a special operations force known for executing dangerous and often classified missions around the globe, Surmont saw a chance to define himself. Within the first 15 minutes of the elite and grueling training program in Coronado, he finally felt at home.

Over the next decade he learned small unit tactics, weapons systems, communications, explosives, aviation, rappelling, skydiving, maritime operations, navigation and survival skills. He married five years into his service.

As a member of multiple SEAL teams, Surmont taught basic underwater demolition to trainees, earned medals and commendations and survived harrowing experiences among multiple deployments — where he watched in horror events he will only discuss off the record.

Former Navy SEAL John Surmont is shown with the Desert Patrol Vehicle Detachment for Task Force K-BAR at Kandahar International Airport in Afghanistan in this photo from January 2002. Surmont served on the task force as a lead communications expert. (Courtesy of John Surmont).

Former Navy SEAL John Surmont is shown with the Desert Patrol Vehicle Detachment for Task Force K-BAR at Kandahar International Airport in Afghanistan in this photo from January 2002. Surmont served on the task force as a lead communications expert. (Courtesy of John Surmont).

His wife told him there was a noticeable difference between the John that left and the John that came back.

Like tens of thousands of his military brothers and sisters, Surmont suffered from untreated PTSD after leaving the Navy. Cold sweats and the need for an exit plan combined with irritability and sleeplessness. He struggled with this while witnessing the birth of his three children: McKallah, Lucas and Tobias.

“So by 2006, I had three children and a failing marriage,” Surmont said.

He channeled his energy into creating and running Sofcoast, an unmanned aerial systems company. Sofcoast designed and built tethered drones with surveillance capabilities and was cultivating contracts with the U.S. Army. Employees included a former worldwide sales manager from Ford Motor Co. and a retired higher-up from the FBI.

Former Navy SEAL John Surmont, right, gives a demonstration to a congressional staff delegation on San Clemente Island of a small unmanned aerial system in this undated photo. At the time, Surmont was the assistant officer in charge of the Naval Special Warfare Command’s unmanned aerial systems program. (Courtesy of John Surmont)

Former Navy SEAL John Surmont, right, gives a demonstration to a congressional staff delegation on San Clemente Island of a small unmanned aerial system in this undated photo. At the time, Surmont was the assistant officer in charge of the Naval Special Warfare Command’s unmanned aerial systems program. (Courtesy of John Surmont)

Then, on March 21, 2013, Surmont dropped his children off at school and swam laps at a local pool. On his way home, while crossing an intersection in Chula Vista, an 18 wheeler carrying lumber ran a red light.

Surmont’s body was sent through the passenger-side window.

After emergency surgery, doctors documented traumatic brain injury, facial contusions, lumbar damage, fractures, tears, atrophy, psychological damage, memory loss and a severely worsened PTSD.

“That’s where it all started to unravel,” Surmont said.

Navy veteran John Surmont's car is shown being towed after he collided with a truck that ran a red light in Chula Vista on March 21, 2013. Surmont was thrown through the passenger side window of his car in the collision. (Courtesy of John Surmont).

Navy veteran John Surmont's car is shown being towed after he collided with a truck that ran a red light in Chula Vista on March 21, 2013. Surmont was thrown through the passenger side window of his car in the collision. (Courtesy of John Surmont).

Following the accident, he said, “I stuttered. I slurred my speech. I had difficulty sleeping. I had difficulty walking. I had difficulty going outside. I had difficulty interacting with human beings. I had a hard time with decisions — like I didn't know right from wrong.”

He added, “I felt like I was just a grown child.”

His memory and anger worsened after the crash, but he told a doctor at the time that “sunshine helps.” The VA eventually labeled him 80% disabled.

The next two years were a mess. Surmont received a settlement following the accident, but the money didn’t go far after attorney fees and medical expenses. Sofcoast collapsed without its able-bodied leader. Surmont watched as his children moved with their mother to Florida, and though he soon found someone else and remarried, it wouldn’t last long.

He self-medicated, in addition to taking opioids, sleeping pills and anxiety medications prescribed by the VA. He enrolled in therapy for war veterans with traumatic brain injury and PTSD.

Nothing worked. His chronic pain, crippling anxiety and depression weren’t improving.

Surmont thought himself a worthless failure. He often considered jumping from the Coronado bridge over San Diego Bay, but talked himself out of it each time by remembering his children or placing a call to the VA suicide hotline for help.

Confidential support is available if you’re having thoughts of ending your life: (800) 273-8255

During that time the Navy SEAL Foundation, a nonprofit dedicated to the special warfare community and their families, was invaluable to Surmont. The organization helped the veteran with rental assistance and other forms of support. One of its board directors — a SEAL Surmont said he put through training — reached out in 2014 with a suggestion for his old instructor.

Have you heard of TMS, he asked.

Chapter Two: The father, the son and the machine

Dr. Kevin Timothy Murphy learned about TMS the year before Surmont did.

It was the middle of the night, and as was often the case, the 45-year-old doctor was awake. He and his wife, a chief administrator at UCSD, had a 9-year old son with severe and violent autism who didn’t sleep for more than an hour or two at a time.

“It was brutal,” Murphy said. “It almost destroyed our marriage, destroyed our family, destroyed our house. He didn’t make eye contact. It was like having a dog, but it was worse, because he was like a Tazmanian devil.”

Murphy is a tall, full-framed veteran. Several of his former colleagues describe him as charismatic and commanding. He talks very fast, is quick to anger and does not mince words when speaking about people he detests.

Dr. Kevin Murphy gives inewsource reporters a tour of the empty UCSD Center for Neuromodulation on Dec. 6, 2019. (Brad Racino/inewsource)

Dr. Kevin Murphy gives inewsource reporters a tour of the empty UCSD Center for Neuromodulation on Dec. 6, 2019. (Brad Racino/inewsource)

He joined the Navy after graduating from Notre Dame in 1989 and served as an engineer aboard the USS Ranger during the Gulf War. He left after four years of service and earned his master’s degree in neurophysiology at Purdue, then his medical degree from the University of Chicago’s Pritzker School of Medicine in 1998.

After an internship, residency and short stint in private practice, Murphy became an assistant professor and medical director at UCSD’s Department of Radiation Medicine and Applied Sciences in 2005. He worked his way up to become a department vice chairman and has talked at medical summits around the world. Among his many specialties is pediatric cancer care.

“I see about a hundred kids a year,” Murphy said. “Half of them are going to die, but 20% are going to die every year.”

It took a long time, he said, to learn how to separate himself mentally from that dark reality — to take all that anger and frustration and let it go. He said it’s a talent.

But as a father, Murphy couldn’t let go of his son, not without trying everything at his disposal to alleviate what was happening inside the child’s brain.

“All the experts told me the same thing — ‘Your son is going to be in your house the rest of your life. Find a room to put him in,’” Murphy said.

Then, at three or four in the morning, the doctor said, a TV special caught his attention. It was about an adult with Asperger’s who, after participating in a TMS research experiment, suddenly “switched on.” The man, John Elder Robison, was able to understand human emotions, look people in the eye and empathize. Robison eventually wrote a book about his experience.

Intrigued, Murphy searched for local TMS providers and found a clinic between Los Angeles and San Diego called the Newport Brain Research Laboratory.

Newport, like many other providers around the country, practices a personalized version of TMS. They called their treatment MRT, or magnetic resonance therapy.

The treatment involves measuring a patient’s heart rate and brainwaves using an electroencephalogram (EEG), employing proprietary software to analyze that data and deriving a treatment plan from it that includes power settings, location and other variables.

It’s different from standard TMS, which does not measure brainwaves and, depending on the condition being treated, is applied to the same location of the brain each time, within a limited power range and time span.

Though it’s been around for at least 15 years, personalized TMS hasn’t produced enough solid data to gain FDA approval. That means patients generally pay for it out of pocket, instead of using insurance.

Desperate and in a self-described “disaster state,” Murphy drove his son an hour north to Newport Beach. He restrained the child while a technician applied a large paddle to the 9-year-old’s head, then flipped a switch.

A flurry of electromagnetic pulses caused the boy’s neurons to fire in a way they never had before. It was painless.

His son’s treatment continued for the next three months, but Murphy and his wife noticed early on an entirely new development in their home.

“He slept. He never slept,” Murphy said.

The doctor, who had known nothing of TMS, became a convert.

Within months, he struck up a business relationship with the Newport Brain Research Laboratory, though the details of that partnership are disputed in a 2018 lawsuit and countersuit between Murphy and Newport, with wildly varying accounts.

Murphy said he bought his first TMS machine from Newport, installed it in his San Diego cancer clinic in 2014 and began using it to treat “just about everything,” including PTSD, autism, Alzheimer’s, traumatic brain injuries and eating disorders.

“It's one of the more safer devices I’ve ever played with,” Murphy told inewsource.

The building that houses California Cancer Associates for Research and Excellence (cCARE) in the neighborhood of 4S Ranch in northern San Diego is shown on Feb. 2, 2020. Dr. Kevin Murphy, a radiation oncologist at cCARE, also operates his personalized TMS clinic out of the building. (Zoë Meyers/inewsource)

The building that houses California Cancer Associates for Research and Excellence (cCARE) in the neighborhood of 4S Ranch in northern San Diego is shown on Feb. 2, 2020. Dr. Kevin Murphy, a radiation oncologist at cCARE, also operates his personalized TMS clinic out of the building. (Zoë Meyers/inewsource)

In its lawsuit, Newport claims its scientists made frequent trips to Murphy’s cancer practice to teach the oncologist how to use and interpret their software, in the process disclosing to him their secret formula. Murphy denies this.

“I understand the brain a little bit better than these guys,” he said.

Asked to respond to Murphy’s statement, a Newport spokesman told inewsource this month that its “team has over 100 years of cumulative neuroscience experience with contributions from neurosurgeons, neurologists, PhD's, physicists, and engineers,” and that “Newport stands behind its excellent results and safety record.”

Though Newport had succeeded in helping Murphy’s child sleep, the boy still wasn’t speaking. Murphy said he asked Newport technicians to target the parts of his son’s brain that deal with auditory processing and speech, but they refused because it was not part of their treatment.

“Well, I'm going to do that, because we should be doing that,” Murphy recalled saying. “I radiate the brain. I'm pretty comfortable treating this anatomy.”

His son was among his first patients.

The doctor said that after several months of administering electromagnetism to his child’s brain, the boy’s handwriting and mood improved, and he began speaking. The change is evidenced in a video Murphy shows clients, potential investors and reporters as part of a slideshow presentation.

Contact the reporter

Do you have information that could further inewsource’s investigation that you’d like to share with reporters?

Contact Jill Castellano:

[email protected]The first clip shows the child before treatment, acting wildly in the house, with his mother restraining him and telling him to breathe. In the post-treatment clip, the son sits calmly, speaking to the camera, composed and coherent:

“So basically, if I wouldn't have had autism, Dad wouldn't have started this whole thing. He's going around the world! Showing pictures of my drawings, my handwriting ... and tons of other things!”

Today, Murphy said, his son still lags behind with social interaction, but he goes to high school and is remarkably different than how he used to be.

By late 2014, Newport employees and Murphy were working out of an office in Del Mar. In its lawsuit, Newport said it set up the space for Murphy to treat patients using its technology, and supplied all the equipment and staff. Murphy’s counterclaim disputed that and said he paid his own expenses and “conducted his own research.”

Murphy later told inewsource that wasn’t exactly true.

“Using the word ‘research’ — that would be probably not as accurate as saying, ‘It was practice of medicine and treating patients,’” Murphy said.

“I’ll try to get better at that.”

In February 2015, a troubled Navy SEAL walked through the doors at Del Mar suffering from depression, anxiety, sleeplessness and aggression. An initial mental health screening classified him as “markedly ill,” and his family psychiatric history was marked “unknown.”

“How did you find out about us?” the form asked.

“Navy SEAL Foundation,” the veteran wrote.

Johnathan Surmont, meet Kevin Murphy.

Chapter Three: From grisly origins

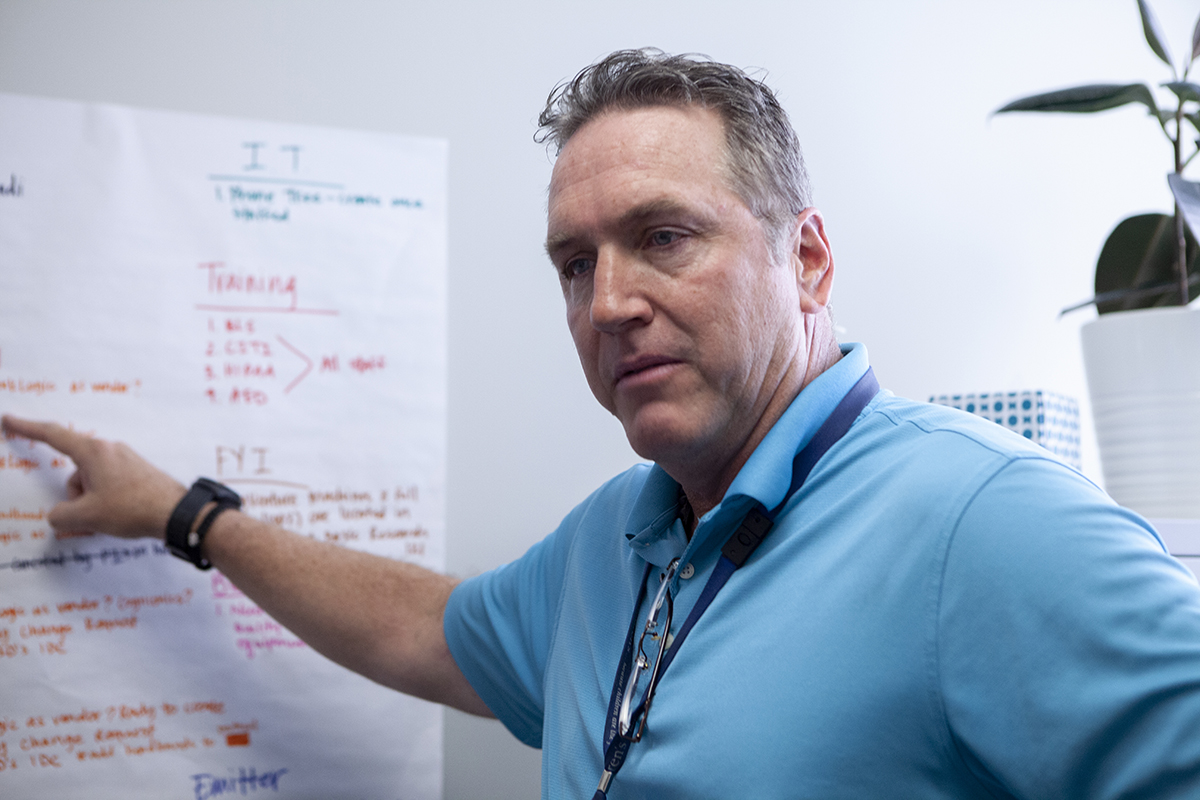

Surrounded by onlookers, Italian physics professor Giovanni Aldini stood over a fresh cadaver at the Royal College of Surgeons in London in 1803. The body on the table in front of Aldini belonged to a 26-year-old man recently hanged for drowning his wife and child in a nearby canal.

Using makeshift batteries of zinc and copper, Aldini applied an electric current to the corpse — first to the mouth and ear, which made the jaw quiver and left eye open, then to the rectum, which convulsed the entire body “as almost to give an appearance of reanimation.”

A short while later, Mary Shelley published “Frankenstein.”

An illustration of a corpse revived by a primitive galvanic battery published in 1836. (Courtesy of Library of Congress)

An illustration of a corpse revived by a primitive galvanic battery published in 1836. (Courtesy of Library of Congress)

Aldini’s experiments were groundbreaking but only one step toward a better understanding of how electricity and magnetism affect the human body. Future strides in the field included the discovery of electromagnetic induction, the invention of electroshock therapy and the first use of an electromagnetic pulsing device to evoke muscle contractions.

And as with many new discoveries, some doctors went too far with it.

In 1874, American physician Robert Bartholow explored bioelectricity in muscles and nerve fibers by applying electricity to the head of a Cincinnati housewife. It worked — he elicited slight muscle twitches — then he increased the power until “distress, convulsion and eventually coma were reported.” The housewife died within 72 hours.

Nearly a century later, two doctors from Tulane University used a combination of electrical stimulation and forced heterosexual actions to “cure” a patient of homosexuality in what “many modern practitioners consider the darkest hour for brain stimulation,” according to an ethics paper on the topic.

But it was English physicist Dr. Anthony Barker and his colleagues in 1985 who induced a hand twitch using magnetic stimulation to the brain. TMS was born.

Over the next 35 years, researchers on every continent (except Antarctica) have studied and improved upon the technique, testing its efficacy on more than 450 conditions, from alcoholism and back pain to vision disorders and wounds.

TMS is a treatment — not a drug or device — and the FDA regulates the machines that deliver it and the marketing surrounding it. Buoyed by convincing research outcomes, the FDA approved the first TMS device and its marketing in 2008 for treating major depressive disorder. Medicare billings for TMS took off over the next decade, from at least eight providers billing for the service in 2012 to at least 144 in 2017, according to an inewsource analysis of data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Further clinical trials using TMS on other illnesses produced robust data, and the FDA approved certain TMS devices to treat migraines in 2013 and obsessive compulsive disorder in 2018. A European regulatory agency has approved the treatment for other conditions, such as chronic pain and Parkinson’s disease.

“FDA approval is a pretty high scientific bar,” said Dr. David Feifel, a psychiatrist who spearheaded TMS treatment at UCSD more than a decade ago. He spoke to inewsource while standing between two TMS machines at his Kadima Neuropsychiatry Institute in San Diego.

“You really have to demonstrate in a rigorous, scientific way that the treatment, whether it's a device or medication, is efficacious,” Feifel said.

Dr. David Feifel, a psychiatrist and founder of UC San Diego's TMS program, is shown outside his Kadima Neuropsychiatry Institute in La Jolla on Oct. 8, 2019. (Zoë Meyers/inewsource)

Dr. David Feifel, a psychiatrist and founder of UC San Diego's TMS program, is shown outside his Kadima Neuropsychiatry Institute in La Jolla on Oct. 8, 2019. (Zoë Meyers/inewsource)

Oversimplified, here’s how standard TMS works:

A magnetic coil is placed over a patient’s scalp at a location dependent on the disorder being treated. The coil delivers a specific number of short bursts of magnetic energy at a certain power that produce tiny currents in the brain. Those currents activate neurons and override the way the brain typically functions.

“We've got 85 billion brain cells which are ostensibly like biological wires,” said Feifel, and those brain cells “use electrochemical systems to fire, and they're talking to each other all the time. It's that firing pattern that produces everything we perceive and everything we feel.”

When our emotions are in an extreme state, like in depression or anxiety, that’s due to parts of the brain malfunctioning, he explained. The idea behind TMS is to use a pulsing electromagnetic field targeted at those specific areas to fix them.

“It's really a new era of treatment,” he said.

A major draw of TMS is that there are no drugs, needles or probes involved. Only a repetitive clicking, like a bug zapper hard at work, along with a tapping sensation. It is considered low risk and side effects include headaches and dizziness.

Treatment typically takes less than an hour. On average, patients undergo four to six weeks of treatment, one session per day, though some may return for booster sessions if the effects wear off.

Melinda Williams Tomes receives Deep TMS treatment at Kadima Neuropsychiatry Institute in La Jolla, Oct. 8, 2019. Deep TMS is FDA-approved and a different treatment than Murphy’s personalized TMS. (Zoë Meyers/inewsource)

Melinda Williams Tomes receives Deep TMS treatment at Kadima Neuropsychiatry Institute in La Jolla, Oct. 8, 2019. Deep TMS is FDA-approved and a different treatment than Murphy’s personalized TMS. (Zoë Meyers/inewsource)

That’s standard TMS. There is another world of TMS that doesn’t stick to these guidelines and is used by practitioners around the country, including Murphy, who use those machines to treat all kinds of ailments without FDA approval. This is known as “off-label” treatment, which accounts for roughly one out of every five prescriptions written in the U.S.

“Off label isn't illegal,” said Jared Cooney Horvath, a cognitive neuroscientist from the U.S. who now works at the University of Melbourne. “Anyone can do whatever the heck they want to do with a device” so long as it's ethically sound and within safety parameters.

And though he imagines some people get around it, he said there also needs to be consent and “a very clear understanding that this is not a proven therapy.”

Chapter Four: Cross circuits

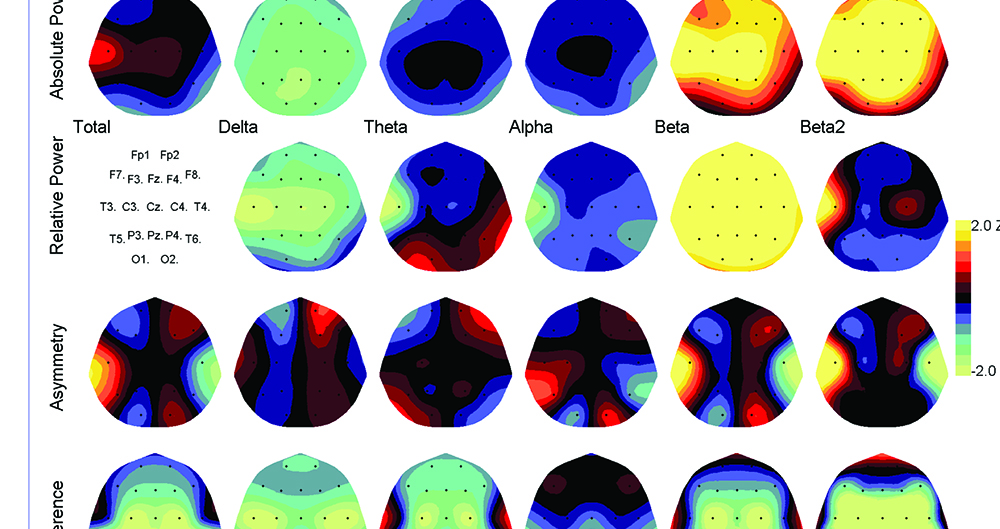

A cap with 19 electrodes recorded Surmont’s brainwaves at the Del Mar clinic in February 2015. A scientist observed:

“Synchronous theta may be indicative of medication or substance use, disrupted sleep cycle, and possible brain injury.”

Check. Surmont was taking sleeping pills, pain medication, antidepressants and smoking medical marijuana. A disrupted sleep cycle and brain injury had been issues for years.

“Observed multiple frequency synchronous alpha activity may be associated with confusion of incoming information, disrupted sensory and executive functions.”

Check. Surmont complained upon intake of an inability to focus, collect his thoughts and find the right words.

“Spectral analysis reveals diffuse activities present in all bands which may be related to a feeling of hypervigilance, restlessness, difficulty feeling calm and a feeling of being overwhelmed by sensory stimuli.”

Check, check, check and check.

Recommended treatment: Magnetic Resonance Therapy — the brand name for Newport’s personalized TMS — along with “sunlight.” Surmont returned the next day to start treatment and later slept through the night for the first time in more than a year.

“I pushed the ‘I believe’ button at that point,” Surmont said.

Electroencephalogram (EEG) readouts of John Surmont’s brain while visiting the Newport Brain Research Laboratory in May 2015. (Medical records courtesy of John Surmont)

Electroencephalogram (EEG) readouts of John Surmont’s brain while visiting the Newport Brain Research Laboratory in May 2015. (Medical records courtesy of John Surmont)

Murphy was Surmont’s attending physician in Del Mar, and the veteran was instantly enamored.

“A veteran naval officer — very tall, handsome, intelligent, commanding presence,” Surmont said.

But Murphy wasn’t always around. He was balancing his full-time UCSD duties with growing Newport’s brand: serving on their advisory board and touting Newport’s magnetic resonance therapy during trips to military bases, a charitable foundation and the Pentagon.

“This technology was created and has been honed by a group of brilliant researchers and scientists at the Newport Brain Research Lab,” Murphy said in a statement on a now-defunct webpage soliciting donations. He added that Newport’s scientists “have revolutionized the field of neuroscience with these breakthroughs in understanding the brain.”

“Right now it’s like we’re selling snake oil,” Murphy told The Washington Post for a January 2015 story about Newport’s treatment.

“It’s hard to believe, and if I hadn’t had my own son treated, I wouldn’t have believed it,” he said at the time.

Surmont was keeping busy as well. During his treatments, he met writer and TV producer Grant Scharbo. Surmont shared his life story with Scharbo, including his struggles with PTSD and his frustrations with the VA health care system.

“His initial story sparked an idea for me for a TV show called ‘The Siege,’” Scharbo told inewsource. “It was fictional, but basically about a group of former Navy SEALs who take over a hospital in the Rocky Mountains to help a brother in need.”

Surmont served as a consultant on the project, putting Scharbo in touch with other veterans, helping the writer with authenticity and detailing exactly how SEALs would seize a hospital. The two pitched and sold the idea to Fox, then wrote a pilot episode.

It never made the cut.

“At its core it's a pretty heavy topic — that the greatest American heroes of our time have trouble getting proper medical treatment,” Scharbo said.

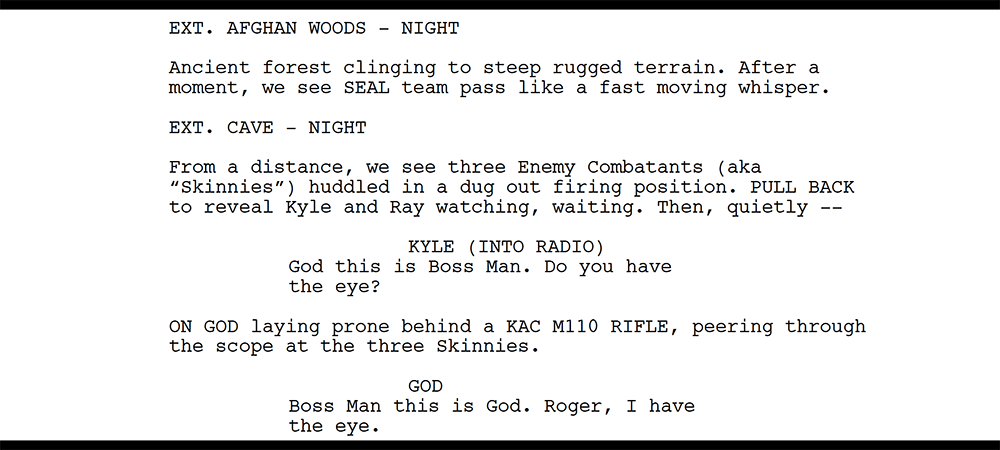

Script from "The Siege," a TV show pilot Surmont worked on with writer and producer Grant Scharbo. (Courtesy of Grant Scharbo)

Script from "The Siege," a TV show pilot Surmont worked on with writer and producer Grant Scharbo. (Courtesy of Grant Scharbo)

Years later, Scharbo still remembers what moved him the most about the experience. It was Surmont’s way of thanking him for trying to give voice to a community that, by its ethos, is often voiceless: Surmont gave Scharbo his Navy SEAL trident pin.

“Or he tried to give it to me, but I refused to take it,” Scharbo said. “Among SEALs, that's the highest honor. It's the pin they slap onto the coffins.”

From February through May of 2015, Surmont went through 63 treatments of Newport’s Magnetic Resonance Therapy. By the end, the veteran said he hadn’t felt that good since before his accident. His PTSD was essentially gone, according to his self-assessment. He had no repeated memories of stressful military experiences, no feeling distant from other people, no angry outbursts or trouble sleeping and no thoughts of his future being somehow cut short.

The father of three spent that summer with his children, who were visiting from the East Coast, and he and his second wife engaged in talk therapy sessions.

Things were also looking up for Murphy.

The doctor used the TMS machine he bought from Newport to treat his private practice cancer patients at a San Diego clinic called cCARE, but at different settings and brain locations than Newport’s providers, he said, and the new technique was successful.

“It turned into a melee of patients hearing about it, rumors about how good it was working, people in the lobby saying, ‘Please treat me,’” Murphy recalled.

San Diego philanthropist Charles Kreutzkamp was one of them. Kreutzkamp’s cancer treatment prompted a common side effect called chemobrain, which includes thinking and memory problems, and Murphy believed he could fix those symptoms with personalized TMS.

After beginning brain stimulation treatment, Kreutzkamp “started to stand up and walk out of his wheelchair and mentate clearly,” the doctor told inewsource, and the philanthropist was so impressed by Murphy’s work that he asked how he could help.

“I need $10 million,” Murphy recalled telling Kreutzkamp, reasoning that five research trials on his technique would cost around $2 million each.

When Kreutzkamp died in November 2015, his family trust allotted $10 million to the UC San Diego Foundation, a nonprofit that accepts and manages private gifts for the university. It would take more than a year, however, before Murphy could spend the money.

Meanwhile, the effects of Surmont’s treatments began to wane. The “ups and downs” were back, he told a VA nurse in the summer of 2015, and he returned to Del Mar for another 17 sessions in November and December.

It was around that time when Murphy noticed cameras throughout his shared office space with Newport, equipped with audio and video wiring. He believed Newport’s scientists were spying on him.

“To me, I was now under surveillance,” Murphy told inewsource. “They were trying to figure out what I was doing in my own corner, getting these different results than they were getting, pushing the science.”

Murphy believed there was a nefarious connection between Newport’s employees and China. In his 2018 lawsuit, Murphy said Newport’s CEO “openly bragged about his purported ties to the Chinese People’s Liberation Army,” and another Newport higher-up “bragged that he had uncles who were Generals in the Chinese Army.” During one of his interviews with inewsource, Murphy showed reporters a printout of Newport’s key personnel, taken from its old website, and pointed to the Chinese connections referenced in their respective biographies.

“You should look into those guys,” Murphy told reporters.

In its lawsuit, Newport claims Murphy told retired U.S. military leaders that the organization “is comprised of Chinese spies, Chinese Mafia and Chinks” in an effort to discredit his former colleagues and “obtain military business for himself.” The suit named more than six people Murphy allegedly said this to, including a retired Marine colonel and a retired Navy admiral.

“Newport never engaged in surveillance of Dr. Murphy,” a Newport spokesman told inewsource.

“Newport, like most research based institutions, uses security cameras, without audio capabilities, in common areas throughout its research facilities. Newport categorically denies any affiliation between its employees and the Chinese government,” he said.

"Any judgment of a person based on their racial or national origin is repugnant and an offensive racial stereotype that has no place in our society.”

Surmont said Murphy confided his suspicions about being surveilled, and the veteran was on his doctor’s side.

“I'm hearing a veteran naval officer, doctor, say these things, who’s my hero, and I'm thinking, ‘I know how that game goes — that's some deep water that you're in, Dr. Murphy,’” Surmont recalled.

Surmont offered a surveillance sweep of Murphy’s office and provided a $3,000 estimate. Murphy declined and said he instead turned to the chief counsel for UCSD’s health system, who advised him to move out of the Del Mar location. The fallout from that academic relationship is also detailed in an accompanying inewsource investigation.

Murphy stopped communicating with Newport and opened a new clinic. It was in the same building as cCARE, the established cancer practice in northern San Diego.

Shortly after, an argument between Surmont and his wife in February 2016 made the veteran feel like a worthless, hopeless failure. Again he thought of taking his own life — deciding against it on his way to the Coronado bridge. He showed up at the San Diego VA the next morning for more counseling and told a psychiatrist he was “broken” but wanted to live.

“There are more moments than I care to admit where I'm kind of white-knuckling things to appear normal, while there are so many things going on underneath," Surmont said at the time.

He turned to Murphy.

“Murphy's position was, ‘I'll treat you for the rest of your life, no charge. I care about you,’” Surmont said. “That's when I made the fateful decision to just start going to Murphy.”

From May 2016 to July 2017, hardly a week went by without the veteran getting PrTMS from his “hero” at the new San Diego clinic, his medical records show. Surmont befriended Murphy’s staff, learned about the science behind the TMS machines and was there so often Murphy gave him an office.

Navy veteran John Surmont at Dr. Kevin Murphy’s clinic to receive PrTMS treatment on April 28, 2017. (Courtesy of John Surmont)

Navy veteran John Surmont at Dr. Kevin Murphy’s clinic to receive PrTMS treatment on April 28, 2017. (Courtesy of John Surmont)

Dr. Kevin Murphy treated former Navy SEAL John Surmont so often that the doctor gave the veteran office space. Surmont is pictured at Murphy’s clinic on April 28, 2017. (Courtesy of John Surmont)

Dr. Kevin Murphy treated former Navy SEAL John Surmont so often that the doctor gave the veteran office space. Surmont is pictured at Murphy’s clinic on April 28, 2017. (Courtesy of John Surmont)

“I thought Dr. Murphy walked on water,” he recalled. “I lauded him, I praised him, I told everybody I could about the benefits of this therapy.”

At the time, Murphy was building a practice around a therapy new to him while trying to alter it. One challenge was that he wanted to create a software that took data from the EEG cap, which records the brainwaves, and turn it into a treatment plan for the TMS machine, which delivers the therapy and has plenty of settings to choose from. Essentially, he wanted to automate the process and remove himself from determining the best dose for his patients.

Murphy worked on creating that software over the next two years through a “trial and error method,” the doctor said. He needed patient data to train the software to determine which settings worked best on which brainwaves.

“There was a lot of tinkering,” Surmont remembered, describing how the doctor would adjust different settings on the TMS machine and ask for feedback.

“He was learning as he goes,” he said.

That didn’t bother Surmont — he was willing to try anything, he told Murphy. Test away.

It didn’t work. Surmont’s problems persisted throughout 2016. His second marriage was faltering and he was using cocaine, which he also told Murphy.

“I would disclose to him if I had a difficult weekend, or if I had any kind of a struggle,” Surmont said. His medical records back this up, showing he used cocaine several times and continued to rely on medical marijuana for pain and sleep.

Murphy kept treating him.

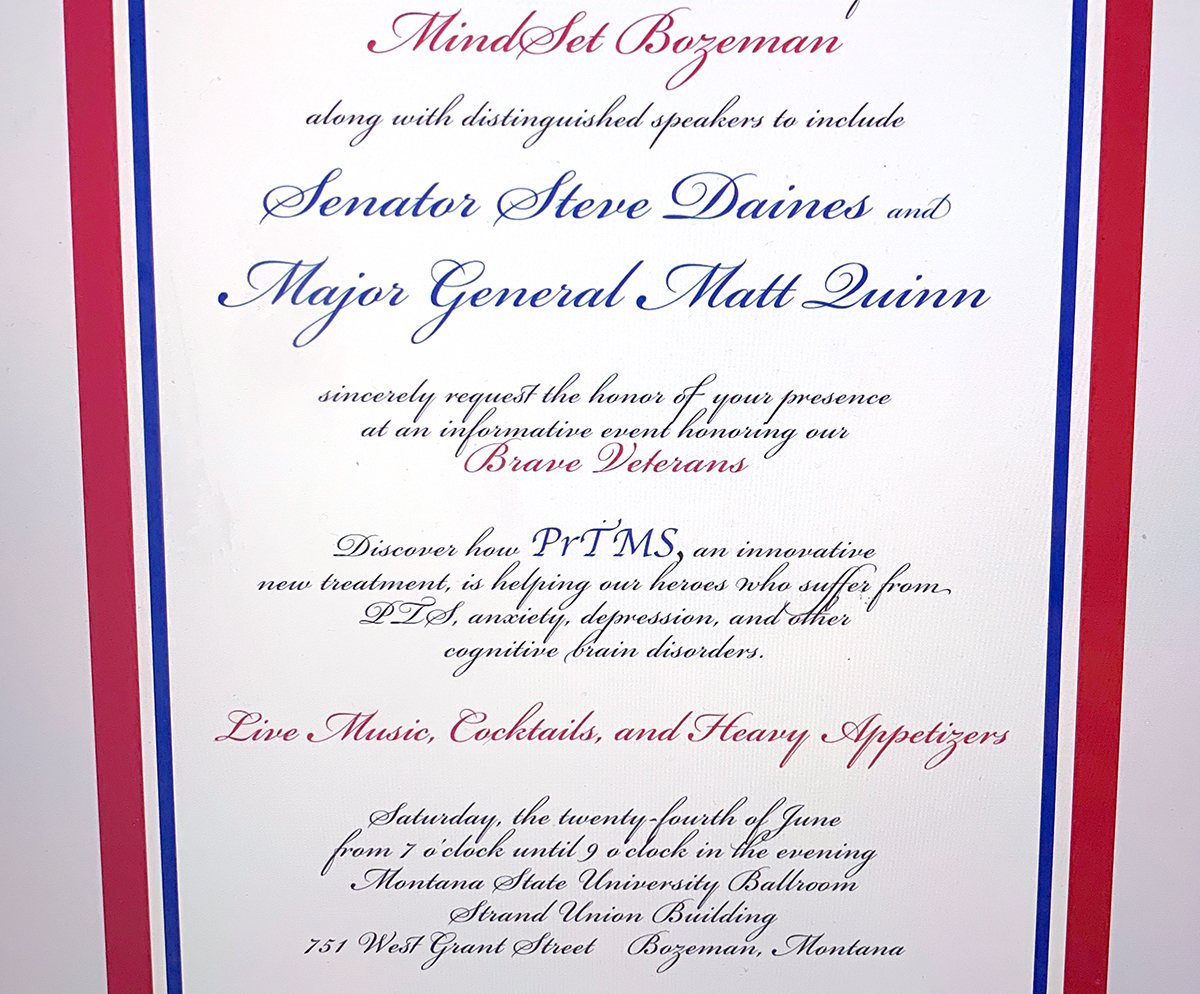

Still in a hole in October 2016, Surmont flew to Montana to visit SEAL friends who wanted to help. Even though he was there because of severe depression, he couldn’t stop himself from extolling Murphy and his promising treatment. He put one of his friends, a doctor, in touch with Murphy, and the two began discussions about opening a PrTMS clinic in Bozeman, Montana.

It would be named after Surmont.

A PrTMS event took place in Bozeman, Montana, roughly eight months after John Surmont visited his SEAL friends in the state.

A PrTMS event took place in Bozeman, Montana, roughly eight months after John Surmont visited his SEAL friends in the state.

Less than two weeks later, Surmont was back in San Diego at Murphy’s to continue treatment. That fall, he applied to graduate school for a master’s degree in clinical psychology with an emphasis on marriage and family therapy. Murphy wrote Surmont’s letter of support:

“John is not only an intelligent and hard-working person, but he has dedicated himself to enriching the lives of fellow veterans and their family around him. ... He is a kind, compassionate, intelligent, and strong person who has a clear sense of direction and purpose.”

Surmont was accepted into the program in December 2016 and wrote about TMS for a midterm. He told Murphy’s staff he was finally realizing what he wanted out of life and had a sense of clarity when thinking about his future. He felt like he could “finally breathe.”

Then, on his 159th personalized TMS treatment on Jan. 4, 2017, Surmont’s medical records noted a change.

“[Patient] states that he is extremely happy and he feels like evil has left his life and he is out of the darkness ... is displaying manic behavior, he was talking and singing loudly” throughout treatment.

One of the risks of TMS is its ability to induce mania, said Todd Hutton, president of the national Clinical TMS Society and chief medical director of the Southern California TMS Center.

Mania is a “distinct period of abnormally and persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood” along with “abnormally and persistently increased goal-directed activity or energy” lasting at least one week, according to the American Psychiatric Association.

In extreme cases it can lead to a psychotic episode.

Hutton said that if TMS prompts manic symptoms, “generally what we do is we will stop treatment, or at least reduce the intensity or frequency of treatment to manage” them.

But Murphy didn’t hit the brakes. Surmont’s PrTMS continued, week after week, month after month.

“Yeah, because these people are sick, my friend,” Murphy told inewsource. “What are you supposed to do, stop treating someone?”

The treatments continued after Surmont’s June 7 visit, when he exhibited abnormally high energy, was “very talkative” and couldn’t stay on the same topic of conversation. They continued after his July 6 treatment when he again showed “abnormal behavior such as singing loudly.”

And treatments continued after a mid-July weekend when while at home, Surmont said he “felt a kind of pressure with my brain that I'd never, ever felt before or since, and I didn't know what to make of it other than it was a peculiar sensation.

“Then I had a blinding flash of light,” he said, “and I heard my mother speak to me.”

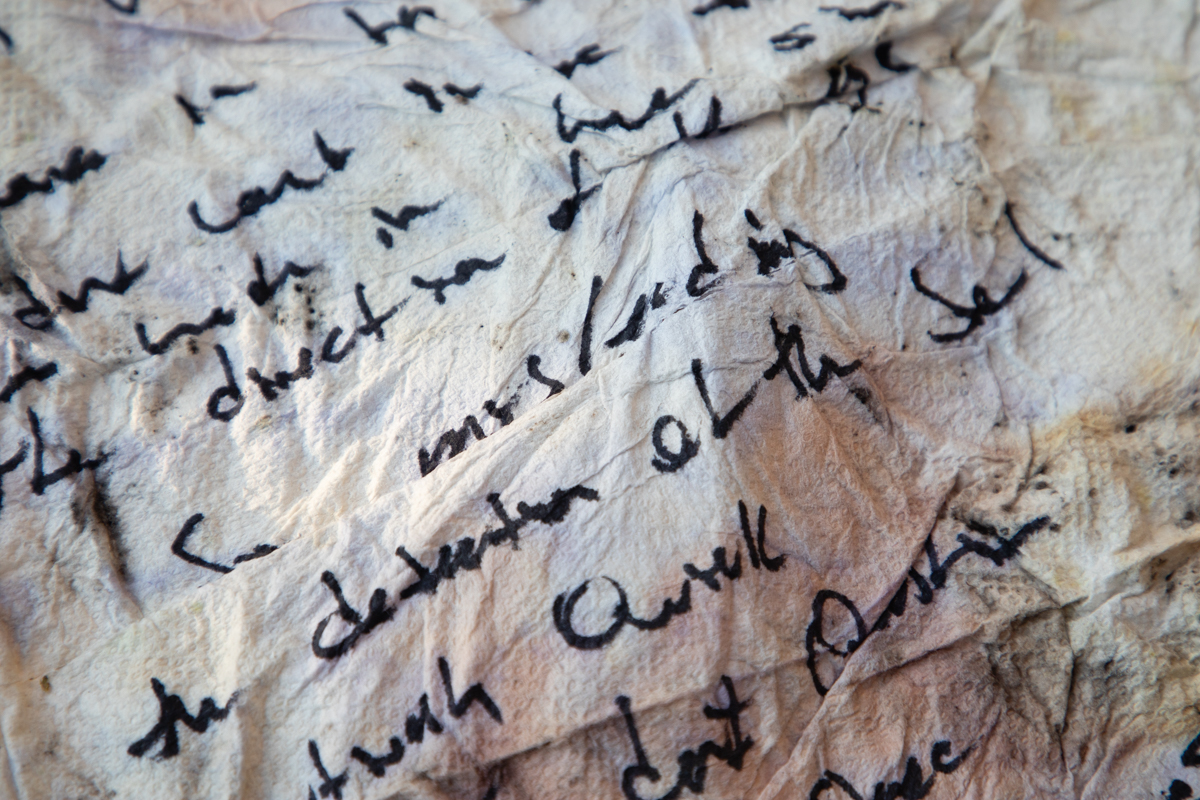

A paper towel stained with wine and written on by John Surmont during the summer of 2017 is shown in this photograph taken on Dec. 19, 2019. (Zoë Meyers/inewsource)

A paper towel stained with wine and written on by John Surmont during the summer of 2017 is shown in this photograph taken on Dec. 19, 2019. (Zoë Meyers/inewsource)

Surmont’s brain was wide open, he said, and he could interact with everything around him. He spent hours communicating with the sun and trees in the backyard. They explained to him how the human and spiritual forms were brought together. He walked through the beginning of time and a tide overtook him.

At one point his 10-year-old son Tobey, visiting for the summer, had a nosebleed. Surmont took the bloody rag, stuck it in a cup, called it the holy grail and hid it in the house.

“I've done drugs. I know when things are crazy and you're tripping out,” Surmont recalled, “and that was not it.”

“I started having an inner dialogue. I didn't hear a voice, per se, but it was more of a sensation of a sifting through the remnants and the details of memories in my mind. And then essentially having someone add a new header file to all of those memories. Somebody added new metadata about the pictures and it wiped out all the other metadata … it was weird. It was like everything was being re-indexed. All of the memories, everything. It was a bizarre feeling.”

He showed up to Murphy’s clinic for treatment again on July 24. Though he had written “atheist” on his intake form with Newport two years prior, he told Murphy’s staff that day that he had found God. PrTMS continued.

The following day, during another treatment, the veteran again showed “abnormally increased energy and socially unacceptable behaviors during treatment i.e. singing at an abnormally loud volume disturbing other patients."

By July 26, 2017, Surmont had gone through at least 234 sessions of personalized transcranial magnetic stimulation under Murphy’s care. That day Murphy put Surmont through a PTSD assessment, and the results showed a severely worsened mental state.

Records describe Surmont as “very unstable, upset at staff and incorrigible in the lobby.” He raved about the “cosmic uterus” and his relationship to the Kennedy family. He said he was drinking wine and eating bread as a disciple of Jesus. Murphy said he asked Surmont to get help, but the veteran refused and stormed out of the office.

“It was dangerous,” Murphy recalled. “He's a SEAL. I know he's armed.”

Patient appears today very unstable. Upset at staff and incorrigible in lobby, may be a psychotic episode.

“There was no doctor at the VA to call. There was no person he'd been working with,” Murphy said. “This is the problem with mental health patients.”

But that wasn’t true: Surmont was meeting with VA psychiatrists every few months and with a private practice psychologist, who helped the veteran with depression and sleep disorders, every few weeks. Murphy didn’t communicate with them nor know the psychologist’s name until inewsource told him.

“All these guys are broken,” Murphy said about war veterans.

During inewsource's first interview with Murphy, the doctor claimed that in the six months leading up to Surmont’s psychotic break, the veteran was homeless, manic, doing drugs on the streets of L.A. and hadn’t shown up for treatment.

During inewsource's second interview with Murphy, reporters presented the doctor with evidence disproving each of those statements.

Murphy then said his previous claims were based on his personal belief or opinion, along with the fact that he sees thousands of patients and can’t be responsible for remembering the history of each.

“Maybe the medical records aren't accurate, maybe I didn't sit there every time I saw him and write a full note,” he said, adding that it drives him crazy that anyone would “take the word of someone who's been through what (Surmont) has, and has this much brain injury and everything else, over the doctors trying to take care of him.”

“He's only good at being the victim,” the doctor said of his patient. “He's been a victim his whole life.”

“If you look at the patients in my history who have been the biggest pains in my ass, who have done the most to try and damage me, are the ones I gave free therapy to,” Murphy said.

Back at home, Surmont’s children grew concerned. They had a meeting with their father. He told his kids he wasn’t crazy, just enlightened. But if they all disagreed, he’d get help.

There was a unanimous vote, and the family piled in Dad’s truck for the drive to the San Diego VA psych ward in La Jolla.

It would be the first stop on Surmont’s trip through hell.

Chapter Five: On shaky ground

Surmont aside, 2017 was a banner year for Murphy.

He named the clinic where he housed his practice Mindset and filed an application to trademark his treatment as PrTMS. He created a company called PeakLogic for his software code and founded a nonprofit called PeakMD to accept donations for treating veterans. He began pursuing clinical trials at UCSD with his former patient’s $10 million donation.

He also signed a research agreement in 2017 with the U.S. Department of Defense to test PrTMS. Over a two-week period, Murphy treated 18 special operations personnel in a “proof of concept” evaluation to determine whether the U.S. Special Operations Command should pursue formal research studies using the treatment. The overall goal, according to the agreement, was “improving human performance” in special operations forces.

“The bottom line is, if you treat these guys, they sleep better, and they perform better,” Murphy explained.

The part of a Magventure TMS machine that allows the treatment to be customized is pictured in the UCSD Center for Neuromodulation on Dec. 6, 2019. (Brad Racino/inewsource)

The part of a Magventure TMS machine that allows the treatment to be customized is pictured in the UCSD Center for Neuromodulation on Dec. 6, 2019. (Brad Racino/inewsource)

Two years later, confident in the proof of concept results, SOCOM executed another agreement with PeakLogic. The agency plans to fund two studies on PrTMS to examine its effects on human performance and on “symptoms experienced by military personnel who suffer from chronic pain,” a SOCOM spokesman told inewsource last month. The studies will be conducted by the Air Force Research Laboratory and Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in the coming months and the agreement is currently awaiting final signature, the spokesman said.

UCSD policy requires its faculty and staff to get approval from the university when conducting outside research, but the doctor never went through that process because it’s his private company engaging in research, he said — not him.

University policy still applies in those kinds of cases.

"Couldn’t care less...,” Murphy said. “Why would I go to those clowns again?"

Murphy secured these contracts and built these businesses without any published research or data backing up his treatment. Everything was anecdotal. Patients flew in from around the world and spread the news back home. Some clinics even added PrTMS as a menu item at their own practice, paying license fees to PeakLogic.

Emails from 2018 show PeakLogic was proposing a $50,000 annual software license fee to investors on top of a $10,000 per patient charge, on average. The emails said clinics could expect to charge patients $20,000 for a course of treatment.

Murphy hopes his software will someday be so advanced that clinics can use it without his help. But for now, the doctor must review every treatment suggestion the software makes, then send his recommendation to PrTMS providers out of state.

That has created a substantial bottleneck.

It’s “probably one of the most difficult bootstrapping exercises I’ve been witness to,” said Chad Nybo, CEO of CrossTx, the company that wrote Murphy’s software code.

Nybo said Murphy is sometimes backed up with about 30 to 40 cases that need review.

“We can see him at five in the morning trying to get caught up before he starts his workday, and on the evenings and weekends,” Nybo said.

Murphy wishes more people would acknowledge his hard work and success rather than setbacks.

“What interests me down the road is why you're not curious about the scores of people who've said we've saved their life,” Murphy told reporters.

inewsource asked Murphy whether the placebo effect could play a role in his anecdotal success.

“There’s always a chance. That's why you need to have a trial to prove it,” he said.

He had already attempted at least two PrTMS trials before accessing the Kreutzkamp fund.

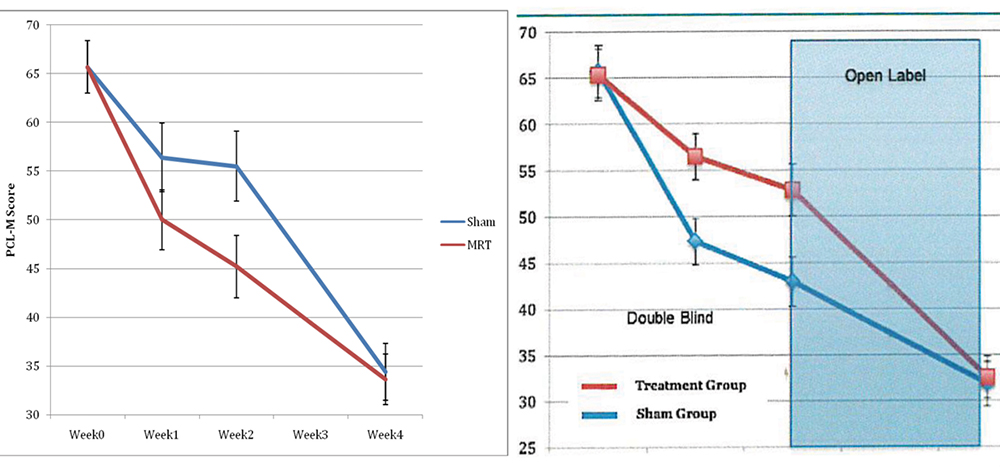

One he pitched to the San Diego VA in August 2016 to gauge how PrTMS fared treating patients with PTSD. Murphy’s research proposal included details of a previous study he said he’d performed along with data — in a four-week trial, 36 combat veterans saw a 65% drop in their symptoms after PrTMS, he said. He included two charts showing the efficacy.

Yet the data, charts and details were not Murphy’s: He took them from a Newport study — which tested Newport’s technology — and kept his competitor’s language verbatim throughout sections of his proposal, substituting the word “PrTMS” in place of Newport’s “MRT.”

inewsource asked Newport about the similarities. A spokesman replied, “Newport discontinued its relationship with Dr. Murphy in 2015, and has never had any association with his treatment protocol.”

He continued, “Newport was asked by inewsource to examine the charts and data that Murphy submitted to the San Diego VA, and to our amazement, can confirm that they are from a Newport study.”

Dr. Harold Garner, an ethics expert and associate vice provost for research development at Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine, reviewed both Murphy’s VA proposal and Newport’s study for inewsource.

“This is what would be considered by scientific professionals to be plagiarized material,” Garner said.

“If Murphy cannot produce laboratory notebooks from whence the data came, it would be considered fabricated or falsified data.”

He added, “It is up to UCSD if they desire to do something.”

Murphy’s explanation for what happened is lengthy and at odds with statements he made previously to inewsource and in court filings. The entire exchange is here.

Dr. Kevin Murphy’s proposal to test PrTMS on veterans with PTSD (right) took language from a previous study performed by his competitors (left) and substituted the word “PrTMS” in place of “MRT.” (Document courtesy of Kevin Murphy and Newport Brain Research Laboratory)

Dr. Kevin Murphy’s proposal to test PrTMS on veterans with PTSD (right) took language from a previous study performed by his competitors (left) and substituted the word “PrTMS” in place of “MRT.” (Document courtesy of Kevin Murphy and Newport Brain Research Laboratory)

The VA project never progressed, but the same month it was pitched, UCSD’s institutional review board — which protects the rights and welfare of human research subjects — met and reviewed another Murphy proposal. This one involved testing PrTMS on children with neurodevelopmental disorders. The board didn’t approve the study.

“From the information that the Committee could find through various sources, it was not clear that the presentation of the safety of prTMS is accurate, especially in children as young as 4 years,” the board noted.

Murphy was undeterred. He knew his treatment worked and was safe, since he’d treated so many patients already without incident, he said.

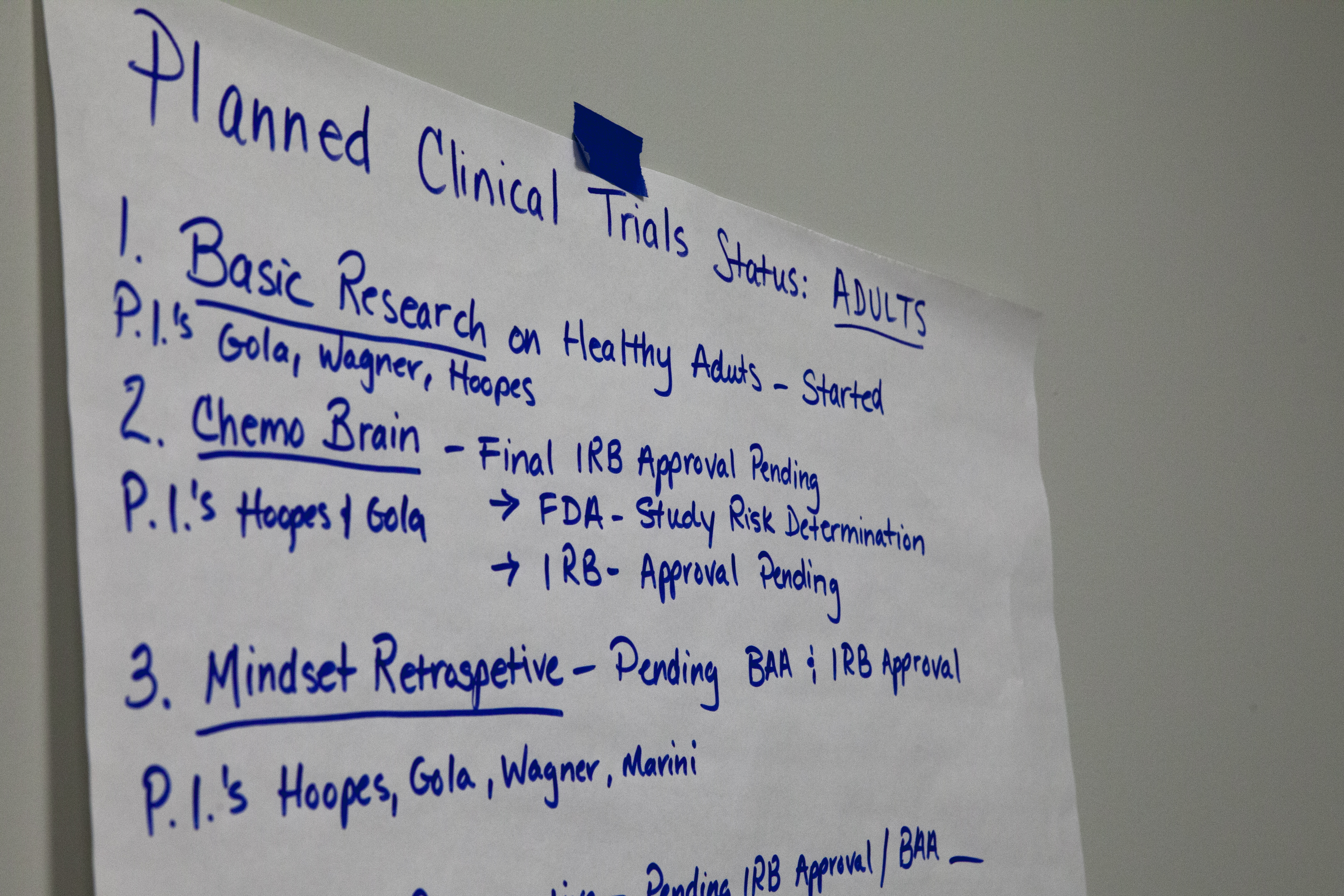

After the $10 million gift from Kreutzkamp finally made its way to UCSD, Murphy went full-bore, planning several more clinical studies along with two retrospective studies — which look back on old data — and a basic research component to test how TMS works on healthy volunteers.

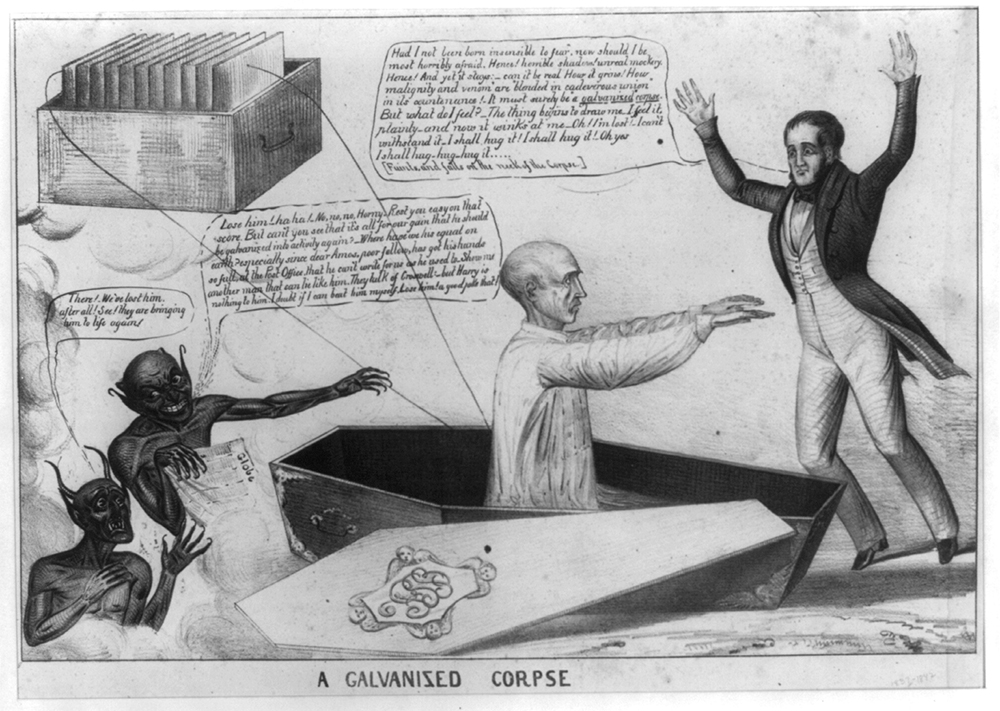

A large sheet of paper detailing Dr. Kevin Murphy’s anticipated research on PrTMS is stuck to a wall in the conference room of the UCSD Center for Neuromodulation in San Diego on Dec. 6, 2019. (Brad Racino/inewsource)

A large sheet of paper detailing Dr. Kevin Murphy’s anticipated research on PrTMS is stuck to a wall in the conference room of the UCSD Center for Neuromodulation in San Diego on Dec. 6, 2019. (Brad Racino/inewsource)

Murphy’s way of approaching treatment, which is supposed to include truthful statements to patients about efficacy, is questionable, according to experts who reviewed the doctor’s website and transcripts of his interviews with inewsource.

Murphy’s old consent form — the one Surmont filled out — didn’t specify that PrTMS lacked FDA approval and clinical research to support it, and it didn’t mention potential side effects.

“Consent says, ‘Here's what you can expect, here's the evidence, here's where I'm coming in,’” said Cooney Horvath, the neuroscientist. “And if he's not being beyond clear with that stuff, then I would say he's on real shaky ethical grounds.”

Dr. Robert Klitzman is a professor of clinical psychiatry and director of the bioethics master’s program at Columbia University. He told inewsource there is no legal requirement for clinicians to disclose that a treatment is being used off-label. However, he said, “Ethically, I think they should.”

“This is info that, presumably, a reasonable person would want to know,” Klitzman said.

Robert Klitzman, shown in this undated photo, is a psychiatry professor and director of the bioethics master’s program at Columbia University. (Courtesy Robert Klitzman)

Robert Klitzman, shown in this undated photo, is a psychiatry professor and director of the bioethics master’s program at Columbia University. (Courtesy Robert Klitzman)

The website for Murphy’s clinic said PrTMS is “based on a solid foundation of existing clinical evidence, as well as ongoing studies,” and that it is “expected to receive FDA approval in 2020.” Interested patients who explored the site further learned that PrTMS is better than standard TMS for treating ADHD, anxiety, autism, concussions, depression, OCD, PTSD and sleep disorders. In fact, PrTMS has a “90% response rate” when treating those conditions, Murphy has said. That claim has been repeated among clinicians licensing his treatment.

All those statements are either untrue or based solely on Murphy’s opinion — though potential patients wouldn’t know that. His claims about PrTMS having a foundation of clinical evidence, conducting ongoing studies and receiving FDA approval in 2020 were removed from his website after inewsource pointed them out.

The rest remain as of early February.

And although Murphy told inewsource twice that he never says PrTMS is FDA approved, reporters found the doctor’s website did say that. An old flyer for his clinic repeated the claim and added that his therapy “has a greater than 20 year track record of safety.”

“Would I be able to read this and generally come away with what I would consider an informed understanding of what's going on?” Cooney Horvath said after reading Murphy’s website. “The answer has to be an unequivocal no.”

Anna Wexler, an assistant professor in the Department of Medical Ethics and Health Policy at the University of Pennsylvania, agreed.

“He's stepping over the line,” Wexler said.

To say PrTMS is a better treatment option than what’s currently available, she said, “is a very clear, misleading claim, especially given that he's not posting any studies.”

Wexler is the lead researcher at the Wexler Lab, which studies the ethical, legal and social implications of emerging technologies. She spoke to inewsource after carefully reviewing Murphy’s website and said the doctor’s language is targeting desperate people.

“I think vulnerable is the right word here,” she said. “I think they may be particularly vulnerable to claims that this new technique or this new technology can solve their problems, especially one that requires up to $10,000 and going into the office every day, five days a week for four to six weeks.”

Off-label use of a novel treatment such as personalized TMS can be appealing to vulnerable populations — people who have exhausted more established forms of treatment. It can also appeal to physicians looking to cash in, which drives Cooney Horvath mad.

“I'm not going to lie. I stepped away from this field because it's such a disgusting little cesspool,” he said, explaining it’s not unique to TMS but rather brain stimulation as a whole.

Jared Cooney Horvath is a cognitive neuroscientist from the U.S. who now works at the University of Melbourne. (Courtesy of Jared Cooney Horvath)

Jared Cooney Horvath is a cognitive neuroscientist from the U.S. who now works at the University of Melbourne. (Courtesy of Jared Cooney Horvath)

He said he believes the majority of doctors and researchers are doing things right and care about the outcomes, “but it's so sexy that it lends itself to this group of individuals who see it as a cash cow and technically there’s nothing you can do.”

Not speaking about Murphy specifically, Cooney Horvath continued:

“People are still selling it and making mass amounts of money, making all these claims that it's going to make you a better athlete, it's going to make you a better this, it’s going to make you a better that. That's why I just had to walk away because you could stand up all day and shout, ‘Look, this dude is lying to you,’ but no one wants to hear that.”

Two experts also took issue with Murphy, an oncologist, overseeing mental health treatment for illnesses he may not fully grasp.

“He should not be treating PTSD, depression, anxiety, autism — any of those indications,” Wexler said. “He should not be the primary care provider for individuals suffering from those disorders.”

Nearly 96% of physicians who billed Medicare in 2017 for TMS are psychiatrists, according to an inewsource data analysis.

Feifel, a Clinical TMS Society board member, feels strongly that TMS “should be given by a board certified or board eligible psychiatrist with training.”

But, he added, “Sometimes we see people veering out of their area of training to treat diseases that they really don't have the experience with because there's an exciting device or it may have a good business model that's associated with it.

“And I think that's really problematic because I wouldn't treat somebody for heart disease as a trained psychiatrist, no matter how straightforward or compelling a machine was to treat it. I need to know a lot more about that patient.

“There’s a lot of things that can go wrong,” he said.

Murphy hired a psychiatrist to join Mindset, his private PrTMS clinic, in late 2019 — four years after opening the practice. Asked why he didn’t have one on staff prior, Murphy replied, “We didn't have need for it.”

“There wasn't enough patients or enough reasons to think I needed somebody,” he said.

Murphy said his psychiatry colleagues at UCSD were angry when he ventured into their field, and he doesn’t dance around his feelings regarding that profession.

“The psychiatric community treats the mind. They don't treat the brain,” he said.

“I'm more a neuroanatomist and brain radiation guy. I'm used to treating anatomy. They don't. They treat your feelings and your subjective presentation, how you manifest. We just fix your brainwaves. They don't like it. A lot of my psychiatry colleagues, they don't understand it. They don't understand physics.

“Ask them the anatomy of the brain, they don't know it,” Murphy said.

Chapter Six: Supernova

Surmont’s first podcast episode, “Unicorns & Dragons,” is a rambling, fictional short story that starts with a “guardian” coming to Earth, then shifts into a biographic retelling of Surmont’s traumatic past. He refers to himself as “the father” throughout the tale.

“One day, the father was called home again, then returned, as a very bad motor vehicle accident had left him crushed physically and spiritually. The father became discouraged by the soulless court system that decided what the father's flesh was worth, while the soulless family court system decided his ancestral bindings were worth nothing …”

“He returned to continue his mission — supernova,” he said.

Less than 24 hours after recording the podcast, on July 28, 2017, Surmont was sitting across the table from a medical student and resident at the San Diego VA, describing “his discordance from kings” and stating that his blood was the “blood of Christ.”

John Surmont walks around Good Samaritan Hospital in Los Angeles looking for a tree he hid out in for a night in 2017 during a psychotic break, Nov. 6, 2019. (Zoë Meyers/inewsource)

John Surmont walks around Good Samaritan Hospital in Los Angeles looking for a tree he hid out in for a night in 2017 during a psychotic break, Nov. 6, 2019. (Zoë Meyers/inewsource)

“This would likely represent schizophrenia,” a physician wrote in Surmont’s chart at the time, “though he is old for a first presentation.”

Medical records show Surmont displayed erratic behavior for six days as an inpatient. Hyper-religious: He was only there at the request of the Father. Grandiosity: Overheard stating he mostly resembles George Clooney. Tangential: I was a grumpy old frog man before, then two weeks ago I decided to be happy and it scared my kids. Suspicious: If this is real I'm in danger, but if I'm crazy then I'm in a safe place. Isolated: Just tell me what I am and I’ll shut up.

Surmont’s memory wasn’t damaged — years later his recollections align with medical records from the time, and he remembers making a decision while in the VA psych ward.

“I didn't bring up TMS,” he said. “I don't know if I, deep down inside, was in a way trying to keep Kevin Murphy out of trouble.”

The VA diagnosed Surmont with bipolar disorder and discharged him on Aug. 1, 2017, and the veteran was back at Murphy’s clinic less than three hours later, according to medical records.

Surmont said Murphy performed an EEG, then took him into a back room. There, the veteran told Murphy that the Catholic church was very proud of the doctor, that the man in the white robe appreciates everything he’d done and that he will be blessed, Surmont recalled.

“I remember his facial expressions,” Surmont said, “like, ‘OK, well that sounds good John and, uh, we're going to take some time off here and we'll be in touch.’”

It was the last time Surmont would ever see Murphy.

“I’m still hurt and heartbroken by the fact that Dr. Murphy was such a present and important and key figure,” Surmont said. “And then all of a sudden — he's gone.”

Murphy didn’t answer inewsource's questions about that day other than to say, “Surmont was contacted by my office a number of times, and never responded” and “we didn’t discontinue him as a patient.”

Surmont left Murphy’s clinic that day and returned home where, he said, “It just got worse and worse.”

He paced in the backyard talking to himself. He began signaling space, thinking the National Reconnaissance Office was “in on it now” with intelligence satellites monitoring him from high above.

inewsource pieced together what happened next from interviews with Surmont, along with his family and his friends, police reports, court records and a recent trip with the veteran back to the scenes involved.

It began sometime around Aug. 27, when Surmont got in his truck and began following what he thought were “cues.”

In Coronado, he started “chasing cannibals” and tried accessing the city’s military base but didn’t have an ID card. He left and surveilled houses, taking pictures, thinking “this is where the cannibals live.”

“God, it was terrible,” Surmont recalled.

He then drove north to the La Valencia Hotel in La Jolla, handed his keys to the valet and tried to check in, expecting a room was reserved for him. Asked to leave under threat, he found himself standing near La Jolla Cove facing the Pacific Ocean. He threw his phone in the water and his shoes in the trash.

Barefoot, he walked to another hotel where he snuck into an open room, discarded his wallet in a nightstand, ate whatever leftover food he could find and fell asleep.

The next morning, he sat on the balcony waving at people, thinking, “This was all part of the plan.” A hotel employee knocked on the door. Surmont left. He found a BMW, the keys still in the ignition and the door unlocked. Inside lay a coin from the San Diego Catholic Diocese.

He thought, “‘There's my cue. That's my key. This car has been set aside for me. Thank you very much,’” Surmont explained.

More cues took him north in his new ride. At one point, Surmont pulled off the highway into an empty parking lot. There he believed he was in an audition for a film about his life. The camera was rolling. Watch this, he thought.

John Surmont sits outside of the Greyhound bus station in Los Angeles, Nov. 6, 2019. During his psychotic break in 2017, the bus station was one of the first places Surmont went to. (Zoë Meyers/inewsource)

John Surmont sits outside of the Greyhound bus station in Los Angeles, Nov. 6, 2019. During his psychotic break in 2017, the bus station was one of the first places Surmont went to. (Zoë Meyers/inewsource)

Pulling from his SEAL training, he ripped the car apart and removed everything that could track his movements.

Eventually he ditched the vehicle and continued on foot. He knocked on doors — “Were you expecting me?” — and rummaged through trash looking for his next cue. He was in a stranger’s backyard, wearing a sunhat and gardening gloves, thinking, “This is my new life.”

Helicopters passed overhead. Surmont waved hello. Two squad cars pulled up. Surmont lay out on the ground at gunpoint.

They must have hired these guys from Disney, he thought, handcuffed in the back of the police car. “Are you getting a fair rate?” he asked the cops. “Are you enjoying everything? This is amazing. You guys are great.”

Surmont was held for 24 hours, given a psychiatric evaluation then released with a bus token, he said. Someone, he can’t remember who, recommended he find his way to the VA hospital in Long Beach.

New mission.

A street intersection in downtown Los Angeles is shown on Nov. 6, 2019. During a psychotic break in 2017, John Surmont traveled through downtown Los Angeles thinking he was on a SEAL team mission as he was cued to different locations. (Zoë Meyers/inewsource)

A street intersection in downtown Los Angeles is shown on Nov. 6, 2019. During a psychotic break in 2017, John Surmont traveled through downtown Los Angeles thinking he was on a SEAL team mission as he was cued to different locations. (Zoë Meyers/inewsource)

While walking through downtown L.A., Surmont’s old SEAL teammates communicated with him through aircraft: They had set up a safehouse just around the corner. Surmont searched and there it was — a shanty with Tang and old bread inside. He hunkered down overnight while he heard fighter jets scramble above.

Later, in front of the Los Angeles Times printing plant, Surmont wandered as the sun set.

You need any drugs, man? “No, I’m good.” You a cop? “No, I’m not a cop.” Then what are you doing here, man? “I don’t know, I’m trying to figure that out myself.”

Nightfall. He’s attracted too much attention and is being pursued. He sprints to a nearby hospital, but the front entrance is off limits. Construction. He looks around and there they are, revving their engines and pointing.

“Now some of this could have been paranoia, but some of this could have been legitimate,” Surmont recalled.

He scrambles up a tree, covers himself in sap and hides overnight. At daybreak, Surmont climbs down, walks for hours, finds a house with a garden hose and drinks as much water as he can. A garage door is ajar. Maybe bed down for the night here, he thinks. Inside the garage his symptoms worsen.

Instructions about what happens next comes from a galaxy in the Pegasus constellation. There is a gland inside Surmont that will soon go nuclear if he doesn’t remain calm.

John Surmont tries to find a location near downtown Los Angeles where he spent time in 2017 during a psychotic break, Nov. 6, 2019. (Zoë Meyers/inewsource)

John Surmont tries to find a location near downtown Los Angeles where he spent time in 2017 during a psychotic break, Nov. 6, 2019. (Zoë Meyers/inewsource)

“I thought I actually was a nuclear weapon,” Surmont said.

The garage door opens. There are several people, including men who “don’t look like they’re in the hospitality business.” A woman pulls out her phone and calls a number. Surmont is barefoot, naked under a ladies bathrobe. He runs.

Now he’s showering in a strange house. A knock on the bathroom door and he flees naked out a second-story window. He steals clothes from an apartment next door. The cops are coming. He’s walking down the street when two officers spot him. He’s in the back of a police car.

Sept. 2, 2017, 7:35 a.m.:

Officer Perez: “Where did you get that shirt?”

Surmont: “I got it from the house I just broke into.”

Arrested, booked as “John Doe #1” with the Los Angeles Police Department. Released back onto the streets.

“If you can't be seen by a certain time, then they let you go. It's so full. The system is so full,” Surmont told inewsource.

John Surmont recalls experiences from a psychotic break he had in the summer of 2017 while revisiting a bus stop near Seventh Street in downtown Los Angeles on Nov. 6, 2019. (Zoë Meyers/inewsource)

John Surmont recalls experiences from a psychotic break he had in the summer of 2017 while revisiting a bus stop near Seventh Street in downtown Los Angeles on Nov. 6, 2019. (Zoë Meyers/inewsource)

It’s night and he’s walking again. More interactions. More danger.

Cops notice him along the highway, ask where he’s going and if he needs a ride. Surmont gets in the backseat, this time without handcuffs. Officers give him almonds and water.

“You guys must've shown up because you're supposed to. Thank you so much. Let's continue with our mission.”