Top 7 things you should know about inewsource’s REWIRED investigation

By Jill Castellano and Brad Racino

Feb. 18, 2020

inewsource published a two-part investigation last week called REWIRED. The stories detail an experimental brain treatment, a Navy SEAL’s psychotic break and an internal investigation at the University of California San Diego, one of the country’s top research institutions.

Since the articles are lengthy, we compiled the top seven takeaways from the investigation for the TL;DR crowd.

The only thing you need to know going in: TMS stands for transcranial magnetic stimulation, a relatively new medical treatment that uses electromagnetism to affect the brain. Clinical trials have shown TMS is effective in battling major depressive disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder and migraines.

That’s all. So without further ado:

1. A former Navy SEAL underwent hundreds of experimental brain treatments by a UCSD doctor, then had a psychotic break.

Former Navy SEAL John Surmont turned to Dr. Kevin Murphy, at the time a UC San Diego vice chancellor, to treat his traumatic brain injury and PTSD. Murphy used a “personalized” version of TMS that isn’t scientifically proven to be effective. Surmont felt the treatment was helping at first but later began showing signs of mania, like singing loudly at inappropriate times and exhibiting abnormally high energy.

Murphy supervised at least 234 personalized TMS treatments given to Surmont. Eventually the veteran’s manic symptoms became so bad that he self-admitted to the San Diego VA psychiatric ward. After discharge, Surmont went on a weeks-long breaking-and-entering spree in Los Angeles — where he thought he was on a covert military mission — that resulted in several arrests and years of court hearings.

Murphy said he continued to treat Surmont even as his manic symptoms worsened because “these people are sick, my friend. What are you supposed to do, stop treating someone?”

2. The UC President’s Office is investigating Murphy for allegedly misusing a $10 million research donation

A UCSD whistleblower complaint prompted the UC President’s Office to investigate whether Murphy used a $10 million university gift to enrich his private businesses. Murphy denies this, though he acknowledges he wasn’t great at inventory or auditing.

The $10 million was supposed to be used for Murphy to research his experimental brain treatment, but all that research has been suspended while the investigation continues. University officials won’t talk to us until the investigation is complete, but they expect to wrap it up shortly.

3. Experts criticize Murphy’s claims about his treatment’s success and scientific basis

Murphy’s unique version of TMS involves taking readings of patients’ brainwaves to offer each person a customized treatment. The doctor said he’s treated thousands of patients this way who suffer from autism, cerebral palsy, depression, anxiety, ADHD, PTSD, sleep disorders and a bad golf swing — all to great results. He claims his treatment is effective on more than 90% of his patients and that it works better than traditional TMS, which doesn’t incorporate a patient’s brainwaves into the treatment.

However, there is no clinical trial or published research supporting Murphy’s claims. Experts we spoke with were concerned that Murphy was misleading patients, especially vulnerable people who may be willing to try anything if they think it might help with a debilitating condition.

4. Murphy’s technology will be used to treat active duty military

The U.S. Special Operations Command, which oversees the Army, Marine Corps, Navy and Air Force special operations, is expected to soon begin testing Murphy’s treatment on military personnel to examine its effects on “human performance.”

Murphy’s private company, PeakLogic, signed a contract with SOCOM that gives the federal agency the ability to test how Murphy’s treatment improves “symptoms experienced by military personnel who suffer from chronic pain,” a SOCOM spokesman said. It will take place at the Air Force Research Laboratory and Walter Reed National Military Medical Center.

UCSD policy requires its faculty and staff to get approval from the university when conducting outside research, but Murphy told us he never went through that process because it’s his private company engaging in research — not him. University policy applies to all faculty research and doesn’t contain an exemption for private businesses.

5. A former top UCSD attorney is part of the university investigation.

While Murphy was opening his private businesses devoted to his version of TMS, he struck up a relationship with Michael McDermott, who was then the chief counsel of the UCSD health system. McDermott’s job was to give campus health officials legal advice.

We looked through business filings and found McDermott was a corporate officer for one of Murphy’s nonprofits and one of his companies while working at UCSD. McDermott also managed a company that contracted with Murphy’s TMS clinic in exchange for 15% of its revenue. The attorney never listed those business interests on university disclosure forms during his two-year tenure.

During the internal UC investigation, Murphy frequently cited McDermott as proof that he did nothing wrong: The doctor was working with a university lawyer as he opened and grew his businesses, so he figured he had UCSD’s approval.

6. Murphy plagiarized a competitor’s work.

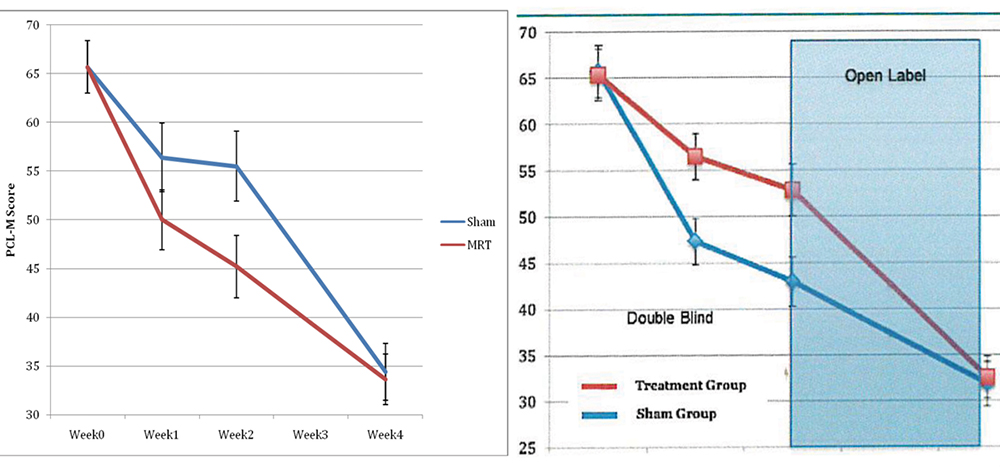

In 2016, Murphy pitched a study to the San Diego VA to test how effective his treatment is for patients with PTSD. Murphy’s research proposal included details of a previous study he said he’d performed, along with data and charts.

The data and charts were not Murphy’s: He took them from a competitor’s study and kept the language verbatim throughout sections of his proposal, except he substituted the name of their treatment for his.

“This is what would be considered by scientific professionals to be plagiarized material,” an expert told us. (You can read Murphy’s explanation for what happened here.)

Dr. Kevin Murphy’s proposal to test PrTMS on veterans with PTSD (right) took language from a previous study performed by his competitors (left) and substituted the word “PrTMS” in place of “MRT.” (Document courtesy of Kevin Murphy and Newport Brain Research Laboratory)

Dr. Kevin Murphy’s proposal to test PrTMS on veterans with PTSD (right) took language from a previous study performed by his competitors (left) and substituted the word “PrTMS” in place of “MRT.” (Document courtesy of Kevin Murphy and Newport Brain Research Laboratory)

7. Murphy repeatedly told us information that wasn’t true or supported by evidence.

Many of the things Murphy told us over 13 hours of interviews weren’t supported by evidence or were incorrect.

For example, Murphy claimed that in the six months leading up to Surmont’s psychotic break, the veteran was homeless, doing drugs on the streets of Los Angeles and hadn’t shown up for treatment. When we presented the doctor with evidence disproving each of those statements, he told us his previous claims were based on his personal belief or opinion, along with the fact that he sees thousands of patients and can’t be responsible for remembering the history of each.

As for the UC investigation, Murphy claims more than a dozen people at the university who had a hand in overseeing the $10 million gift for his research, or worked with him to set up his companies, or worked for him to manage his funds, were incompetent or so jealous of his success that they wanted to see him fail. We couldn’t verify most of those claims.

“I’m on the bleeding edge of this,” Murphy said. “And so everyone’s shooting arrows in my back, going, ‘Stop him. Stop his research. Whistleblower him. We want this. Sue him. Make him look bad. Whatever it takes.’ Because this is really a big deal.”